Випуск 6. Кам’яне мереживо. Вкрадене з Солхату

Історія грабунку кримських пам’яток Ермітажем сягає майже двохсот років: на території півострова працювала безліч археологічних експедицій з Санкт-Петербургу. Одна з найстаріших, що діє й тепер, — Старокримська археологічна експедиція державного Ермітажу. Тож не дивно що більшість знахідок, які походять із Солхату (середньовічне місто XIII—XV ст., що було столицею Кримського Юрту, тепер має назву Старий Крим), вивезені з Криму до Росії за сприяння імперських науковців.

Одним із найпоширеніших типів археологічних предметів з Солхату, привласнених Санкт-Петербургом, є різноманітні архітектурні елементи: різьбленні фрагменти споруд, надгробки, капітелі. Точна кількість знахідок, поцуплених з середньовічного Солхату, невідома. Знакові й найважливіші для репрезентації безперервного розвитку традицій місцевого населення є артефакти, якими росіяни хизувалися 2019 року на виставці «Золота Орда і Причорномор’я. Уроки Чингизидської імперії» в Казані.

Замкóвий камінь, за припущенням керівника експедиції Ермітажу в Старому Криму — Марка Крамаровського, був частиною арки медресе Солхату — найдавнішого мусульманського релігійно-просвітницького закладу на території півострова, побудованого в 1332—1332 роках коштом меценатки Інджи-Бек-Хатун. Залишки автентичного архітектурного оздоблення медресе майже не збереглися до часу археологічних досліджень, і камінь, виявлений під час розкопок наприкінці 1980-х років, є чи не єдиним свідченням запозичень з архітектури Румського султанату (Мала Азія), що розпався за два десятиліття до будівництва медресе.

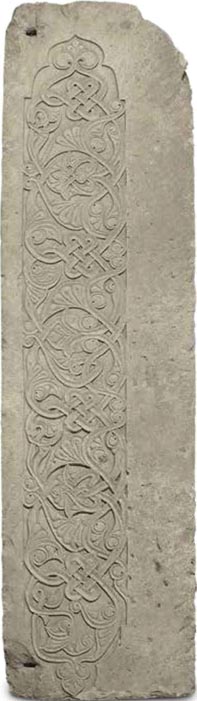

Інший замкóвий камінь, віднайдений під час розкопок 1987/1990 років, походить з мавзолею кінця XІV — початку XV століття. На камені закарбовано ім’я Махмуда ібн Османа аль-Ірбілі, остання частина якого (нісба) вказує на походження архітектора з міста Ірбіль (Ербіль) в сучасному Іраку. Цікаво, що імовірний зодчий мечеті Узбека (1314 р.) — Абдул-Азіз аль-Ірбілі, судячи з нісби, також походив з давнього міста в Месопотамії, що пояснює ранні прояви сельджукської архітектури в Криму.

Якщо переміщення попередніх двох архітектурних елементів із Солхата в Санкт-Петербург вкладається в логіку радянської музейної системи, то привласнення Ермітажем різьбленого блоку, імовірно з облицювання порталу медресе першої чверті XIV століття, нагадує кримінальні хроніки. Під час розкопок кургану Кємаль-Ата в 1994—1996 роках дослідили чоловіче поховання, яке частина дослідників пов’язує із Мамаєм, перекрите двома плитами, покладеними на ребро. Однією з цих плит і була повторно використана плита з облицювання медресе. Цей різьблений камінь із малоазійським орнаментом 2018 року, вже після окупації Криму, «поступив» зі Старокримської археологічної експедиції до Ермітажу. Протягом 24 років один з небагатьох архітектурних елементів першої медресе в Солхаті не передавали до музейних колекцій, а «зберігали», що вчергове ілюструє «російську турботу» про культурну спадщину захоплених територій.

Вже згадану виставку «Золота Орда і Причорномор’я. Уроки Чингизидської імперії» без перебільшень можна назвати квінтесенцією колоніальної політики — презентацією привласненої культурної спадщини поневолених народів. Замкóві камені з медресе Солхату та мавзолею XV століття, різьблений блок з облицювання порталу медресе, капітелі — це не просто архітектурні елементи, а ілюстрація культурних зв’язків середньовічного Солхату із Месопотамією, Золотою Ордою, Анатолією (сучасна Туреччина). Тож вилучення таких предметів з території їх походження, вириває історію Криму з європейського та азійського контекстів. Натомість утворюється все більше місця для міфу про «російський Крим», який старанно поширюють для широкого загалу.

Яшний Денис,

кандидат історичних наук, провідний науковий співробітник Національного заповідника "Києво-Печерська лавра",

аналітик ГО "Кримський інститут стратегічних досліджень".

Release 6. Stone lace. Stolen from Solkhat

The history of looting Crimean monuments by the Hermitage goes back almost two hundred years: many archaeological expeditions from St. Petersburg worked on the peninsula. One of the oldest, still active, is the Staryi Krym Archaeological Expedition of the State Hermitage. Therefore, it is not surprising that most of the finds originating from Solkhat (a medieval city of the 13th—15th centuries, which was the capital of the Crimean Yurt, now called Staryi Krym) were taken from the Crimea to Russia with the assistance of imperial scientists.

Among the most common types of archaeological artifacts from Solkhat, appropriated by St. Petersburg, are various architectural elements: carved fragments of buildings, tombstones, capitals. The exact number of discoveries nicked from medieval Solkhat is unknown. The artifacts that Russians flaunted in 2019 at the exhibition “The Golden Horde and the Black Sea Region. Lessons of the Chingizid Empire” in Kazan are the most iconic and important for the representation of the continuous development of the local traditions.

According to Mark Kramarovsky, the Head of the Hermitage expedition in the Staryi Krym, the keystone was part of the arch of the Solkhat madrasa, the oldest Muslim religious and educational institution on the territory of the peninsula, constructed in 1332—1332 at the expense of the patroness Inji-Bek-Hatun.

The authentic architectural decoration of the madrasa was almost not preserved until the time of archaeological research, and the keystone discovered during excavations in the late 1980s is hardly the only evidence of borrowings from the architecture of the Rum Sultanate (Asia Minor), which fell apart two decades before the construction of the madrasa.

Another keystone, found during excavations in 1987/1990, comes from a mausoleum of the late 14th — early 15th century. The name of Mahmud ibn Osman al-Irbili is engraved on the stone. The last part of his name (nisba) indicates the origin of the architect from the city of Irbil (Erbil) in modern Iraq. It is interesting that the alleged architect of the Uzbek mosque (1314), Abdul-Aziz al-Irbili, judging by the nisba, also came from an ancient city in Mesopotamia, which explains the early manifestations of Seljuk architecture in the Crimea.

If the transfer of the previous two architectural elements from Solkhat to St. Petersburg fits into the logic of the Soviet museum system, then the appropriation by the Hermitage of a carved block, presumably from the cladding of the portal of a madrasa dated the first quarter of the 14th century, reminds criminal chronicles. During the excavations of the Kemal-Ata burial mound in 1994—1996, a male burial that some researchers associate with Mamai was investigated. Two slabs placed on the edge covered the burial. One of them was a reused slab from the madrasa cladding. In 2018, already after the occupation of Crimea, this carved stone with Asia Minor ornament “came” to the Hermitage from the Staryi Krym Archaeological Expedition. For 24 years, one of the few architectural elements of the first madrasa in Solkhat was not transferred to museum collections, but “preserved”, which once again illustrates “Russian care” for the cultural heritage of the occupied territories.

The already mentioned exhibition “The Golden Horde and the Black Sea Region. Lessons of the Chingizid Empire” without exaggeration can be called the quintessence of colonial policy — a presentation of the cultural heritage appropriated from enslaved peoples. Keystones from the Solkhat madrasa and mausoleum of the 15th century, a carved block from the cladding of the madrasa portal, and capitals are not just architectural elements, but an illustration of the cultural ties between medieval Solkhat and Mesopotamia, the Golden Horde, and Anatolia (modern Turkey). Therefore, the removal of such artifacts from the territory of their origin cut out the history of Crimea from the European and Asian contexts. Instead, the myth of “Russian Crimea” takes up more and more space, being diligently disseminated to the public.

Denys Yashnyi,

PhD, research fellow of National Preserve "Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra",

analist of the NGO "Crimean institute of strategic studies"

Замкóвий камінь. Золота Орда. Крим. Солхат. З розкопок мавзолею кінця XІV —

початку XV ст. (1987/1990 рр.) «Державний Ермітаж» інв. № Сол-157

Keystone. Golden Horde. Crimea. Solkhat. From the excavations of the mausoleum of the late 14th —

early 15th (1987/1990) State Hermitage inv. Nr. Sol-157

Замкóвий камінь з ім’ям Османа. Золота Орда. Крим. Солхат. З розкопок медресе XІV ст. (1980-і рр.) «Державний Ермітаж» інв. № Сол-156

Keystone with engraved name of Osman. Golden Horde. Crimea. Solkhat. From the excavations of the madrasa of the 14th century (the 1980s)

State Hermitage inv. Nr. Sol-156

Різний блок. Золота Орда. Крим. Солхат. З розкопок кургану Кемаль-Ата (1994—1996 рр.)

«Державний Ермітаж» інв. № Сол-168

Carved stone block. Golden Horde. Crimea. Solkhat. From the excavations of the Kemal-Ata burial mound

(1994—1996) State Hermitage inv. Nr. Sol-168

Source of illustrations:

Золотая Орда и Причерноморье: уроки Чингисидской империи: каталог выставки, [2 апреля — 6 октября 2019 г., Казань] / авт. вступ. ст. М. Г. Крамаровский.

Golden Horde and Black Sea Region: Lessons of Chingizid Empire: exhibition catalogue, [April 2 — October 6, 2019, Kazan] / Mark Kramarovsky, author of the introductory article.

25.11.2022

Проєкт здійснено за підтримки Стабілізаційного фонду культури й освіти Федерального міністерства закордонних справ Німеччини та Goethe-Institut. goethe.de

The project is funded by the Stabilisation Fund for Culture and Education of the German Federal Foreign Office and the Goethe-Institut. goethe.de