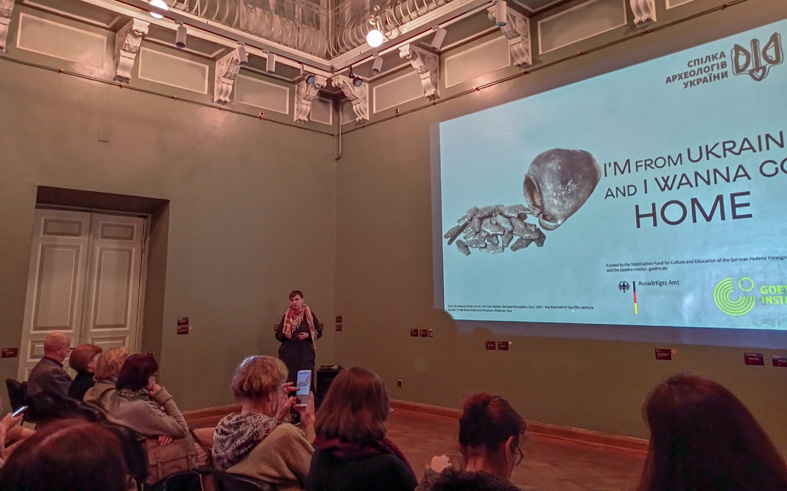

«Археологічна спадщина, вкрадена Росією: інформаційно-просвітницька кампанія».

Настав час підбивати підсумки.

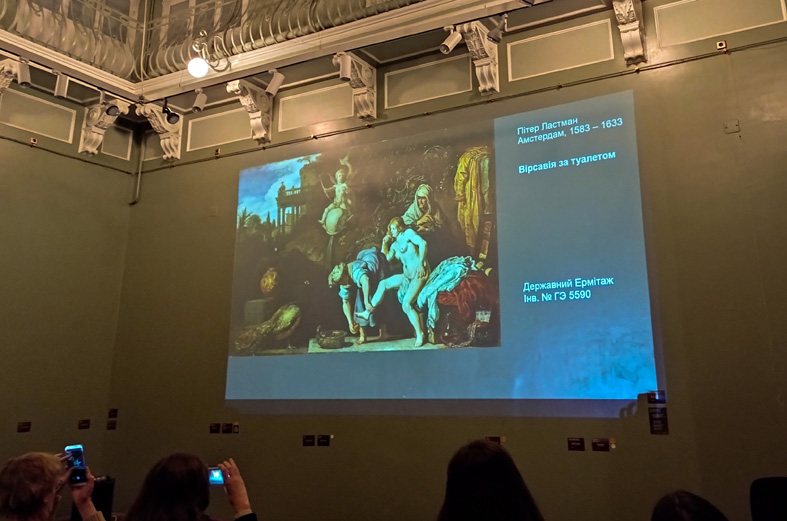

Тому, ми організували зустріч з командою проєкту, представництвом від Гете-інституту, дирекцією Музею Ханенків, музейниками та захисниками культурної спадщини.

Локація заходу не випадкова — Музей Ханенків, стіни якого вже вкотре змушені пустувати, а детективні історії повернення художніх цінностей якого, водночас захоплюють і надихають.

Євген Синиця та Анна Яненко представили результати проєкту, розповіли про імперські практики розграбування та варварське знищення культурної спадщини окупантами, що почалося ще з найперших досліджень археологічних пам’яток на нашій землі. А також трішки поділилися закуліссям: розповіли про неочікувані успіхи та перешкоди в реалізації проєкту.

Олена Живкова, генеральна директорка Музею, розповіла про незаконне привласнення росіянами художніх творів з колекції Музею та історію повернення, щоправда не з музеїв країни-агресора.

Головний підсумок такий: ми лише на початку боротьби за наше минуле, а завдяки підтримці Збройних сил України, наших мужніх і незламних громадян, маємо сили рухатися далі — до нашої Перемоги, усе буде Україна!

Анна Яненко, членкиня ВГО «Спілка археологів України» та авторка випуску 22 про Михайлівський Золотоверхий собор

розповідає про імперські практики грабування української культурної спадщини

Євген Синиця, голова ВГО «Спілка археологів України» представляє результати проєкту

Юлія Ваганова, директорка Національного музею мистецтв імені Богдана та Варвари Ханенків, звертається з вітальним словом

5.02.2023

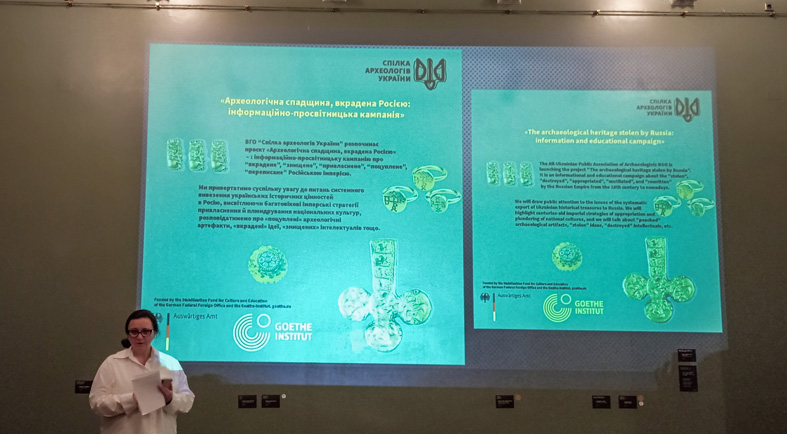

Археологічна спадщина, вкрадена Росією: інформаційно-просвітницька кампанія

The archaeological heritage stolen by Russia: information and educational campaign Випуск 1

Культурна спадщина, зокрема й об’єкти матеріальної культури різних часів, відіграє фундаментальну й визначальну роль у формуванні національної ідентичності, збереженні традицій та цінностей. Питання привласнення, вивезення, викрадення, знищення українських культурних цінностей (зокрема археологічних знахідок) представниками Росії актуалізовано від початку повномасштабного вторгнення і пограбуванням низки українських музеїв (зокрема Мелітопольського). До цієї теми активно зверталися ЗМІ, реагували користувачі соцмереж тощо. Однак, звертаючи увагу на такі випадки, суспільство, здебільшого, не усвідомлює, що ці "пограбування" не окремі прикрі ситуації, а наслідки і результати системної багаторічної імперської політики Росії, спрямованої на привласнення українських культурних цінностей, переписування, а почасти й "вигадування" Росією зручної для неї історії України.

Тому протидія Росії на цьому напрямку гібридної війни є не менш важливою, ніж на реальному фронті. Дієвий спосіб такої протидії країні-терористу — реалізація інформаційно-просвітніх кампаній, а також імплементація інших елементів неформальної культурної освіти.

ВГО "Спілка археологів України" розпочинає проєкт "Археологічна спадщина, вкрадена Росією" — інформаційно-просвітницьку кампанію про "вкрадене", "знищене", "привласнене", "поцуплене", "переписане" російською імперією.

Ми привертатимемо суспільну увагу до питань системного вивезення українських історичних цінностей в Росію, висвітлюючи багатовікові імперські стратегії привласнення й плюндрування національних культур, розповідатимемо про «поцуплені» археологічні артефакти, "вкрадені" ідеї, "знищених" інтелектуалів тощо.

У кожному випуску – окрема історія: про виявлення археологічних знахідок, “механізм привласнення” Росією в дії, викрадення думок й результатів археологічних досліджень, викривлення історії, "викреслювання" людських доль тощо.

Команда проєкту "Археологічна спадщина, вкрадена Росією: інформаційно-просвітницька кампанія"

Release 1

Cultural heritage, in particular, tangible cultural properties from different periods, plays a fundamental and defining role in the formation of national identity as well as in the preservation of traditions and values. The issues of appropriation, removal, looting, and destruction of Ukrainian cultural values (including archaeological artifacts) by representatives of Russia have been mainstreamed since the beginning of the full-scale invasion and heists of a number of Ukrainian museums (for example, the Melitopol Museum). This topic has been actively discussed in mass media; it provoked the reaction of social network users, etc. However, paying attention to such cases, society, for the most part, is not aware that these “thefts” are not isolated unfortunate accidents, but the consequences and results of Russia’s systemic long-term imperial policy aimed at appropriating Ukrainian cultural values and rewriting and/or even "invention" Ukrainian history convenient to Russia.

The resistance to Russia in this direction of the hybrid war is no less critical than in the front of a real war. A practical method of countering the terrorist country is the implementation of informational and educational campaigns and other elements of informal cultural education.

The All-Ukrainian Public Association of Archaeologists NGO is launching the project "The archaeological heritage stolen by Russia”. It is an informational and educational campaign about the "stolen", "destroyed", "appropriated", "mutilated", and "rewritten" by the Russian Empire from the 18th century to nowadays.

We will draw public attention to the issues of the systematic export of Ukrainian historical treasures to Russia. We will highlight centuries-old imperial strategies of appropriation and plundering of national cultures, and we will talk about "poached" archaeological artifacts, "stolen" ideas, "destroyed" intellectuals, etc.

Each release contains a separate story about the discovery of archaeological items, the "mechanism of the appropriation" of values by Russia in action, the theft of ideas and archaeological research results, the distortion of history, the "erasing" of human lives, etc.

"The archaeological heritage stolen by Russia: information and educational campaign" project team

26.10.2022

Проєкт здійснено за підтримки Стабілізаційного фонду культури й освіти Федерального міністерства закордонних справ Німеччини та Goethe-Institut. goethe.de

The project is funded by the Stabilisation Fund for Culture and Education of the German Federal Foreign Office and the Goethe-Institut. goethe.de

Випуск 2

Привласнення Росією артефактів давньої української історії починається одночасно з першими системними розкопками в степах України — вже від другої половини XVIII ст. Однією з перших таких пам’яток став Мельгунівський курган (Лита могила).

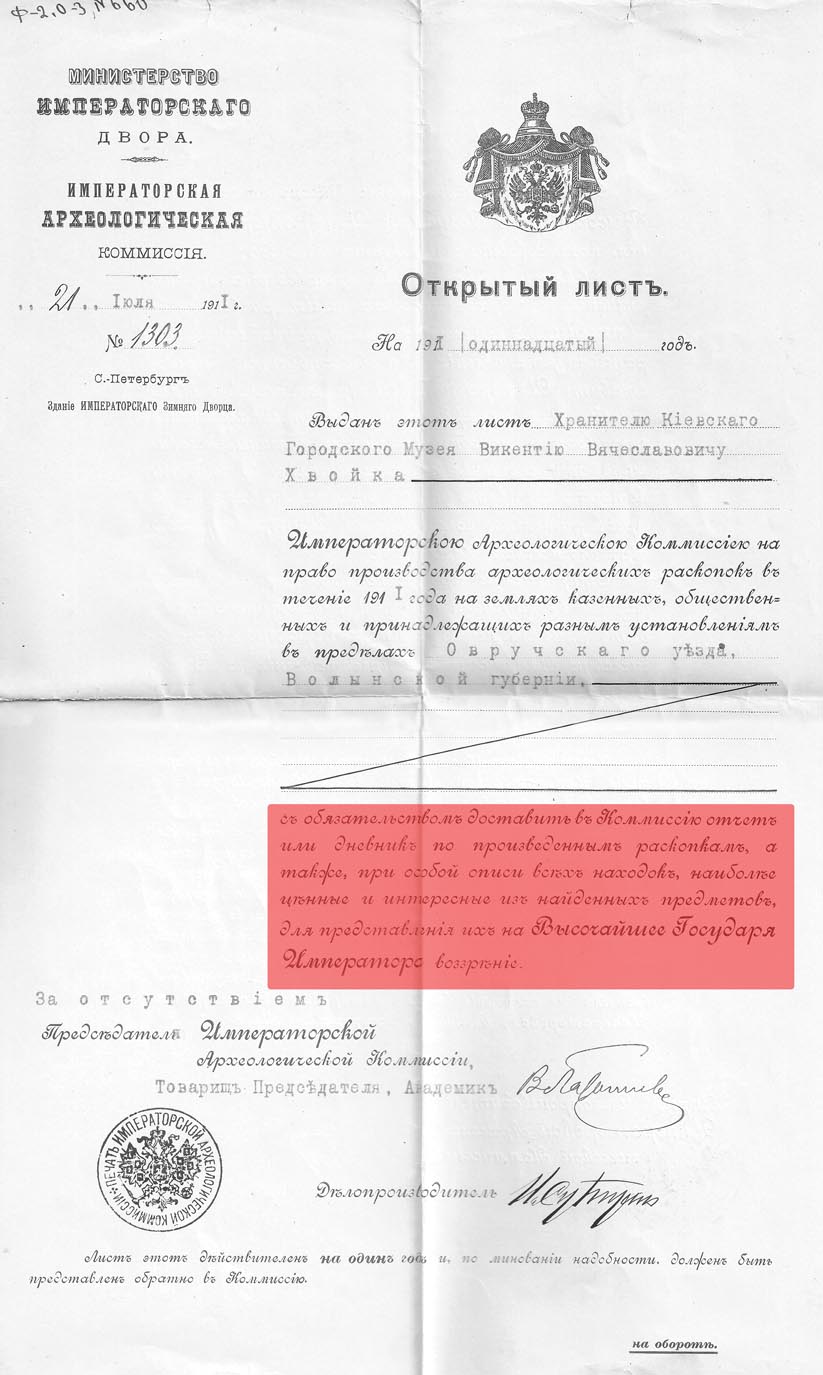

З утворенням 1859 року в Петербурзі державної установи — Імператорської археологічної комісії (ІАК), — проведення польових досліджень (розвідок й розкопок) з метою, передовсім, збагачення колекцій старожитностей імперської метрополії набуло офіційного характеру.

Від 1889 року Комісія стала чи єдиною установою, що видавала “відкриті листи” (дозволи) на розкопки. Відповідно до зарегламентованих правил усі виявлені знахідки представлялися на розгляд Комісії, члени якої й вирішували їхню подальшу долю. Тож зібрання музеїв столиць імперії активно поповнювалися. До того ж доволі часто власне російські дослідники отримували право працювати на українських археологічних об’єктах.

Після встановлення радянської влади на теренах України, практика роботи росіян на українських пам’ятках і подальше вивезення артефактів продовжилась.

>Значно спростило й пожвавило вилучення й привласнення росіянами археологічної спадщини і давньої історії України системне нищення українства перших десятиліть Совєтів — переслідування інтелектуальних еліт, Голодомор, Великий терор, лінгвоцид тощо.

Місце репресованих кремлівською владою українських вчених часто посідали російські науковці, не гребуючи привласненням собі відкриттів, результатів досліджень, гіпотез, а інколи, й текстів попередників (детальніше дивіться виставку “Наказано не знати: українські археологи в лещатах тоталітаризму”)

Чимало артефактів — джерел для реконструкції давньої історії України — вилучили з українських музеїв й передали до Москви упродовж 1930-х рр. Деякі знахідки з колекцій українських музеїв, які нацисти вивезли в часи Другої світової війни, після повернення “дивовижним” чином знов-таки опинилися у Москві чи Ленінграді.

Після анексії Криму у 2014 році, ці ласі в археологічному сенсі території, стали об’єктом “пильної уваги” російських дослідників. Здебільшого колекції з незаконно розкопаних кримських пам’яток російські окупанти вивозять на територію країни-терориста.

Нині, під час широкомасштабного російського вторгнення, маємо документальні свідчення про вилучення (“евакуацію”) колекцій з музеїв, що знаходяться на тимчасово окупованих територіях, зокрема Криму, Херсонщини, Луганщини, Донеччини тощо.

к. і. н., зав. науковою бібліотекою ІА НАН України,

секретар Правління ВГО “Спілка археологів України”

Вікторія Колеснікова

Release 2

Russia started to appropriate artifacts of ancient Ukrainian history at the same time when the first systematic archaeological excavations began in the steppes of Ukraine, namely in the second half of the 18th century. The Melguniv kurgan (Lyta mogyla) was one of the first cases.

In 1859, a state institution the Imperial Archaeological Commission (IAC) was established in St. Petersburg. Since then, archaeological field studies (reconnaissance and excavations), aimed first at enriching the collections of antiquities of the Russian imperial metropolis, acquired an official character.

From 1889, the Commission became the institution that issued archaeological research permits or licenses (word for word “Open Letters”) to excavate. In accordance with the regulations, all discovered finds had to be presented to the Commission for consideration, whose members decided the further fate of artifacts. So the collections of the empire’s museums were actively replenished. In addition, actually Russian researchers quite often got permission to work on Ukrainian archaeological sites.

After the establishment of Soviet power in the territory of Ukraine, the practice of Russians working at Ukrainian archaeological sites and the subsequent removal of artifacts carried on. The systematic destruction of Ukrainians in the first decades of the Soviet era — the persecution of intellectual elites, the Holodomor (Great Famine), the Great Terror, lignvocide, etc. — simplified and boosted the removal and appropriation of the archaeological heritage and ancient history of Ukraine by the Russians.

The place of Ukrainian researchers repressed by the Kremlin authorities was often taken by Russian scientists, who did not feel squeamish about appropriating the discoveries, research results, hypotheses, and sometimes even the texts of their forerunners (for more information take a look at the exhibition "Ordered not to know: Ukrainian archaeologists in the jaws of totalitarianism").

Many artifacts — sources for the reconstruction of the ancient history of Ukraine — were removed from Ukrainian museums and transferred to Moscow during the 1930s.

Some items exported by the Nazis from Ukrainian museum collections during the Second World War, after the restitution in a "miraculous" way ended up in Moscow or Leningrad.

After the annexation of Crimea in 2014, these attractive archaeological territories became the focus of Russian researchers. For the most part, the collections from Crimean archaeological sites illegally excavated by the Russian occupiers were exported to the territory of Russia.

Now, during the full-scale Russian invasion, there is documentary evidence of the removal (“evacuation”) of collections from museums located within temporarily occupied territories, in particular, in Crimea, Kherson, Luhansk and Donetsk Regions.

Viktoriya Kolesnikova,

PhD in history, Head of the Scientific Library of Institute of Archaeology, the NAS of Ukraine,

Secretary of the Board of the Ukrainian Association of Archaeologists

Відкритий лист Імператорської археологічної комісії на дослідження території Овруччини (1911 р.)

із зазначенням вимоги щодо представлення найбільш цінних та цікавих предметів,

знайдених під час досліджень, на огляд імператора (з колекції Наукового архіву Інституту археології НАН України)

Open letter (permit) of the Imperial Archaeological Commission to conduct the study of the territory of Ovruch Region (1911)

containing the requirement to present the most valuable and interesting objects found during the research for the emperor's inspection

(from the Collection of the Scientific Archive of the Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine)

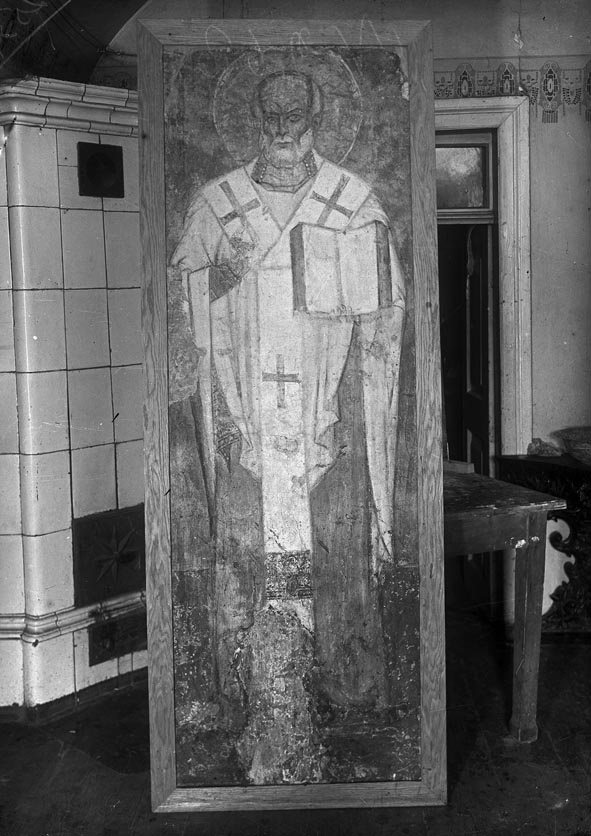

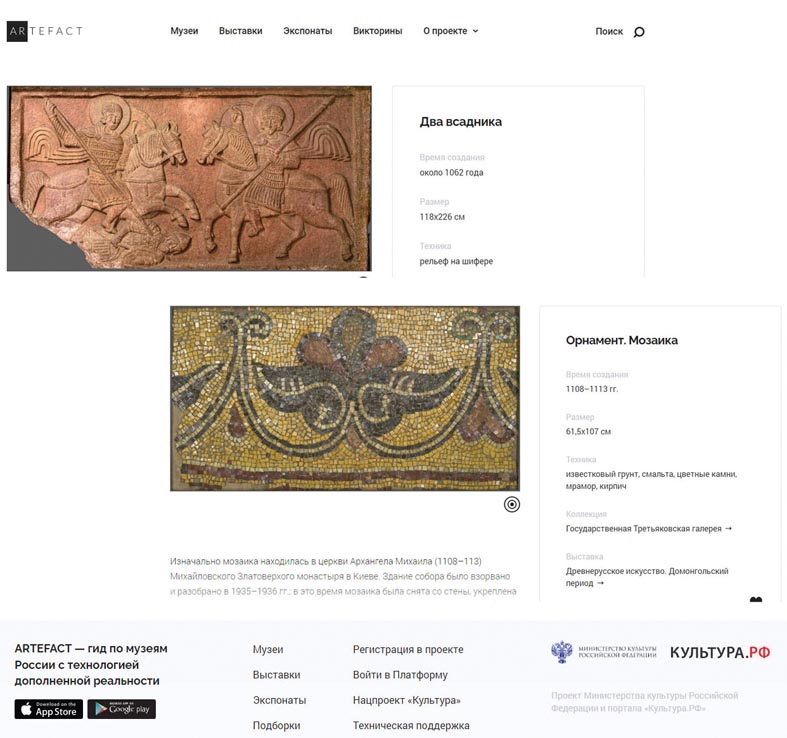

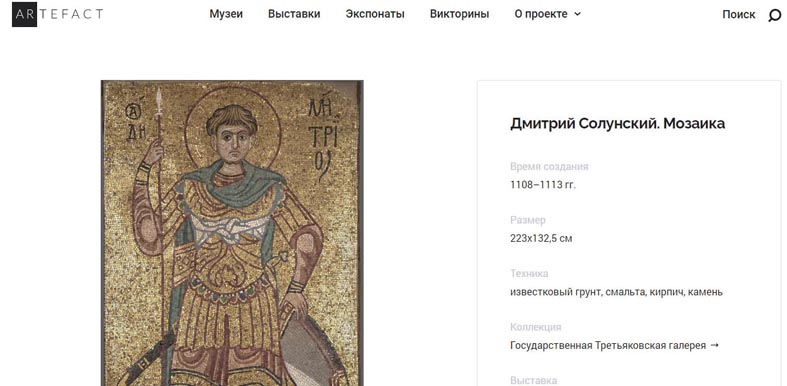

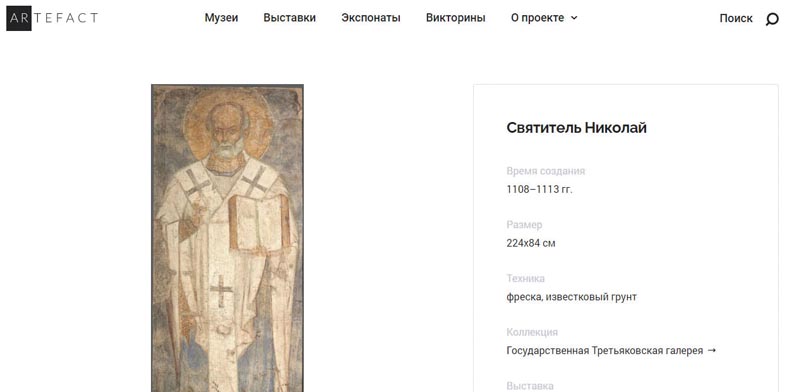

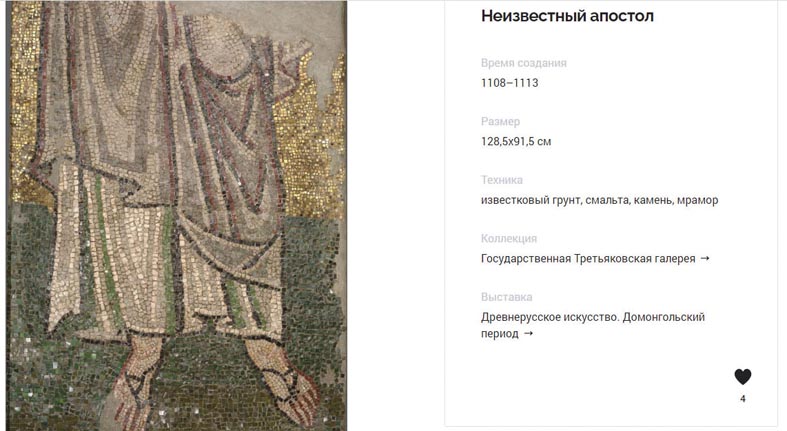

Зал Третьяковської галереї (Москва ) з мозаїками зруйнованого більшовиками Михайлівського Золотоверхого собору, вивезеними з Києва

(за Коренюк Ю. Мозаїки Михайлівського Золотоверхого собору. Каталог. Київ, 2013)

Exhibition hall of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow displays mosaics that had been removed from St. Michael Golden-Domed Cathedral destroyed by the Bolsheviks in Kyiv

(according to Yu. Korenyuk. Mozaics of St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Cathedral. Catalogue. Kyiv 2013)

Допис на російському інформаційному сайті про сенсаційні знахідки російських археологів в анексованому Криму, які поповнять не лише музеї Крима, а й інших регіонів Росії

(фото з матеріалу Радіо Свобода. Кримський автобан – 2020)

Post from Russian information website about the sensational finds of Russian archaeologists in the annexed Crimea, which will replenish not only the museums of Crimea,

but also of the other regions of Russia (according to “Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty” material “Crimean Autobahn – 2020”)

Росіянин виносить награбоване з одного з Маріупольських музеїв (2022 р.) (фото з відкритих джерел)

A Russian takes out looted items from one of the Mariupol museums (2022) (photo from open sources)

31.10.2022

Випуск 3. Лита Могила: перші розкопки — перший грабунок

Вже понад 300 років ординська Московія прагне притулитися до європейської цивілізації. Вкравши разом з назвою історію Русі, хижий сусід й досі прихоплює наше культурне коріння, наповнює свої музеї археологічною спадщиною України. Власне такі яскраві старожитності, які є в нашій землі, на «болотах» відсутні. Час не змінює звички країни-загарбника. Прикладом тому є чергові нещодавні крадіжки — пограбовані росіянами колекції Мелітопольського, Маріупольського, Херсонського та інших музеїв…

А почалась ця ганебна практика ще у XVIII сторіччі з розкопок Литої Могили, що її чужинці нарекли Мельгуновським курганом. Це один з найвідоміших курганів. Його дослідження не лише поклало початок цілеспрямованим археологічним розкопкам на теренах Російської імперії, а й заклало підмурок вивчення старожитностей скіфів.

Роботи на Литій Могилі розпочали на початку вересня 1763 року з ініціативи генерал-поручика Олексія Мельгунова, засланого на південь імперії зміцнювати її нові кордони. Він був наближеним імператора Петра ІІІ, вбитого заколотниками. Тож не дивно, що Катерина ІІ, яка посіла престол по чоловікові, відіслала вельможу подалі від столиці.

Майже десятиметровий поховальний пагорб знаходився в урочищі Кучерові Байраки поблизу Єлисаветграду (тепер — Кропивницький). В теперішніх реаліях — це місцина між селами Топили та Копані Трепівської сільської ради Знам’янського району Кіровоградщини.

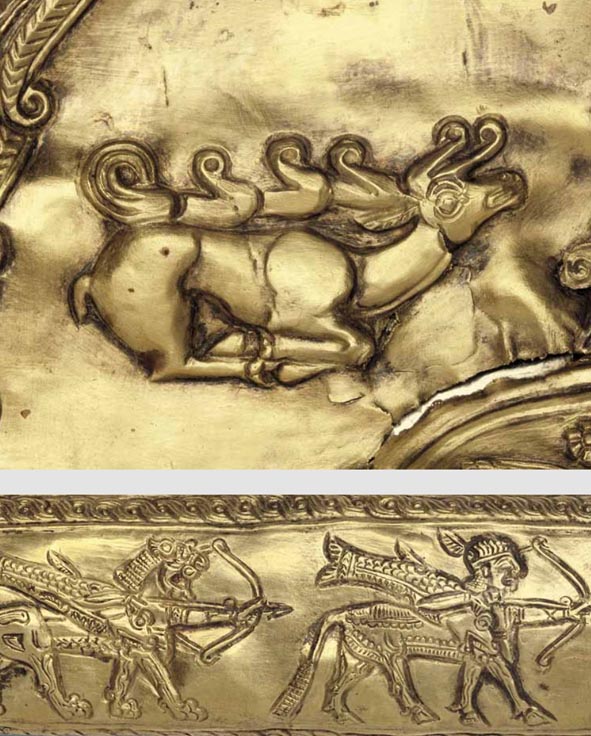

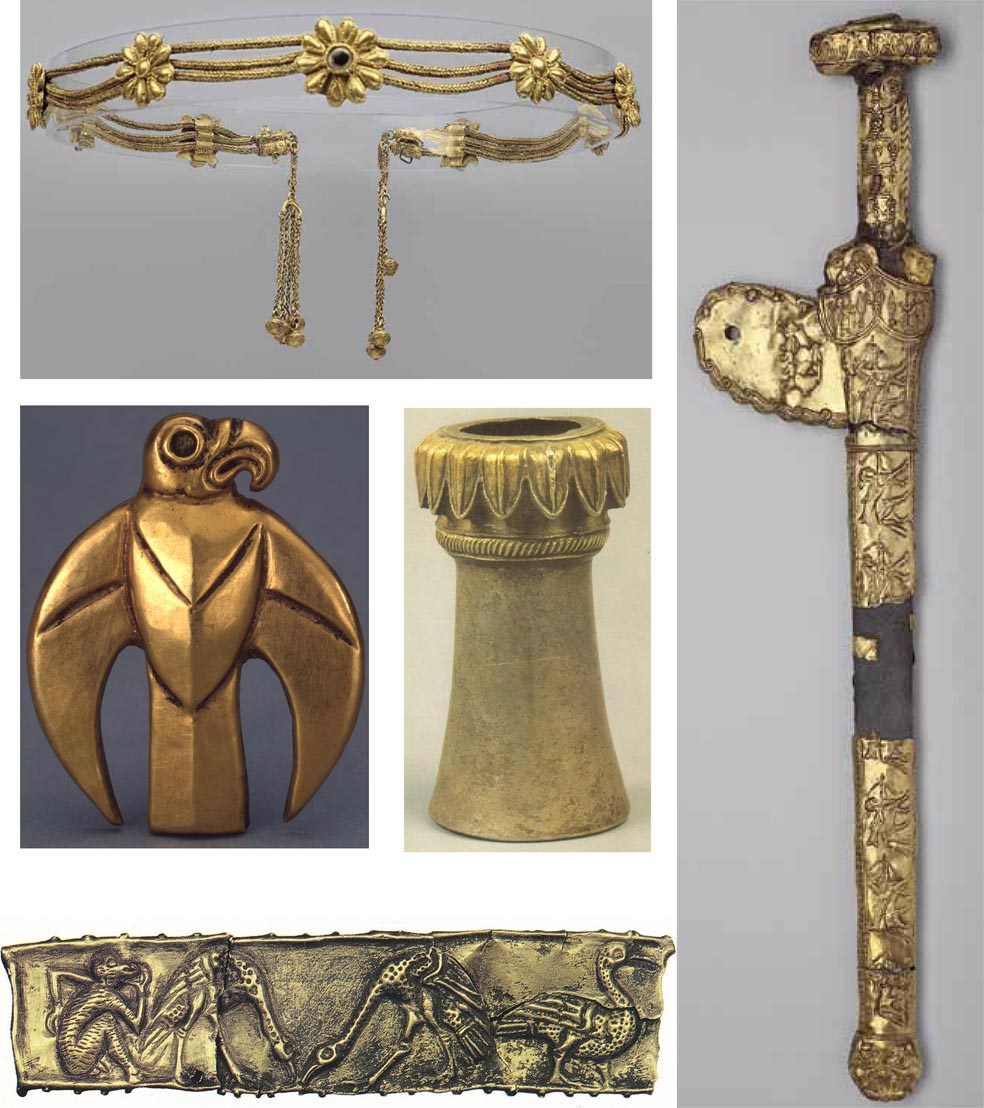

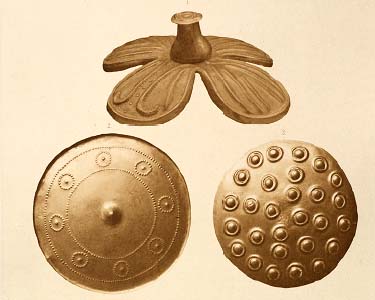

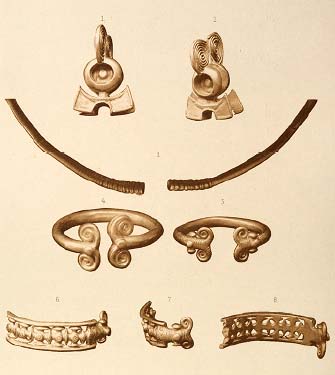

Родзинкою пам’ятки став скарб, що був знайдений в кам’яній скрині під верхівкою її насипу. Згадана скриня приховувала коштовні артефакти, виконані в ассиро-урартському стилі. Це залізний акінак з окутим золотом руків’ям в плакованих золотом дерев’яних піхвах, які вкриті зображеннями фантастичних тварин, срібні елементи від ассирійського палацового табурету, золота діадема, 17 масивних золотих платівок у вигляді орлів, платівки із зображеннями мавп та птахів, бронзова застібка із закінченнями у вигляді лев’ячих голівок, 40 бронзових вістрів стріл. Є всі підстави вважати, що ці предмети належать до другої половини VII ст. до н. е. і були військовими трофеями скіфів, добутими ними під час походів до Малої Азії.

Виявлення скарбу було фактично фіналом робіт започаткованих О. Мельгуновим, периферійна частина насипу Литої Могили залишалася непорушеною. Тож роботи з його дослідження поновлювалися ще двічі, наприкінці позаминулого та наприкінці минулого століть. І лише нещодавно, у 2019 році, експедиція Інституту археології НАН України поставила крапку у вивченні славетної пам’ятки.

З’ясувалося, що курган звели не скіфи, а їхні попередники на цих теренах. Початково основу поховальної споруди склали від 700 до 1000 м куб. дубових колод, привезених за 12—20 км з найближчих байраків. Купа колод, до яких додали ще й інше паливо, стала велетенським поховальним вогнищем, на якому спалили якогось-то достойника. Коштовні поховальні атрибути, що супроводжували елітного небіжчика, згоріли та розплавилися. Шматки ж оплавленої глиняної обмазки споруди, рясно траплялися в цій місцині здавна, що й відбилося в назві кургану.

Під час досліджень 2019 року археологам поталанило відшукати дві платівки з електруму (сплаву золота та срібла), що на диво збереглися у давньому полум’ї. Колись-то ці артефакти з орнаментацією притаманній культурам гальштатського кола, прикрашали стінки дерев’яної посудини. Саме вони дозволяють окреслити вірогідний час побудови Литої Могили. Лише століття, якщо не всі два, по тому скіфи, що тільки прийшли на ці терени, використали для певної культової відправи вже наявний в привабливому місці насип.

Чому саме там знаходиться курган пояснюють старі мапи. Виявляється, могилу спорудили біля найдавнішого шляху України, що в середні віки називали Чорним. Звели на ділянці, що змією в’ється вододілом між верхів’ями Інгульця та Інгулу. І не випадково за 16 км на схід від нього розташовувалося важливе в давнину Чорноліське городище. Цій давній магістралі зобов’язана своїм розташуванням і давня Ольвія, що виникла при броді-переправі через Бузький лиман. Проте, задовго до купців-греків, до городищ Середнього Дніпра цим шляхом ходили торгівельні каравани їх попередників з городища Дикий Сад (м. Миколаїв), що функціонувало за часів кіммерійців.

Втім, повернемося від досліджень ХХІ століття до “досліджень” століття ХVІІІ. Скарб з Литої Могили змінив долю опального царедворця, як змінив і назву пам’ятки. Курган отримав другу назву — Мельгуновський, а Катерина ІІ пробачила Олексію Мельгунову його колишню наближеність до Петра ІІІ.

Знахідки з Литої Могили спочатку потрапили до петербурзької Кунсткамери, звідки їх — у 1859 і 1894 рр. — передали до Ермітажу, де й досі перебуває частина цієї колекції. Позаяк, деякі речі 1932 року все ж таки повернули Україні (до музею Харкова), але ці артефакти загинули під час невдалої спроби евакуації колекцій Харківського історичного музею до Уфи в часи Другої Світової війни.

Насамкінець залишається лише зауважити, що поцуплений скарб дійсно доречно називати Мельгунівським, а самому ж кургану повернути узвичаєну українську назву — Лита Могила.

Болтрик Юрій Вікторович,

кандидат історичних наук, завідувач відділу,

Інститут археології НАН України

Release 3. Lyta Mohyla: the first excavations and the first robbery

For more than 300 years, Horde Muscovy has sought to attach to the European civilization. Having stolen the history of Kyivan Rus along with its name, the predatory neighbour still tries to appropriate our cultural roots and replenish its museums with the archaeological heritage of Ukraine. Actually, “in the swamps”, there are no such striking antiquities as those hidden in our land. The habits of the invading country have not changed with time. Another example is the recent looting of the museums in Melitopol, Mariupol, Kherson and other cities by the Russians... This disgraceful practice started back in the 18th century with the excavations in Lyta Mohyla (Cast Tumulus), which foreigners called the Melgunovsky Kurgan. This is one of the most famous burial mounds. Its research not only marked the beginning of focused archaeological excavations in the territory of the Russian Empire but also laid the foundation for the study of Scythian antiquities.

Work on the Lyta Mohyla started at the beginning of September 1763 at the initiative of Lieutenant General Oleksiy Melgunov, who was sent to the south of the empire to strengthen its new borders. He was close to Emperor Peter III, killed by rebels. Therefore, it is not surprising that Catherine II, who succeeded her husband, sent the nobleman away from the capital.

An almost ten-meter burial mound was located in the Kucherovi Bayraky tract near Yelysavetgrad (now Kropyvnytskyi City). In current realities, this is the area between Topyla and Kopani villages of the Trepiv village council in the Znamyansky district of the Kirovohrad region.

The highlight of the Site was the treasure, found in a stone cist under the top of the mound. The aforementioned cist hid precious artifacts made in the Assyrian and Urartian style. These were an iron akinake-sword with a handle covered with gold in a gold-plated wooden scabbard, decorated with images of fantastic animals; silver elements of a stool from an Assyrian palace; a gold diadem; 17 massive gold plates in the form of eagles; plates with images of monkeys and birds; a bronze clasp with endings in the form of lion heads; and 40 bronze arrowheads. There is every reason to believe that these artifacts belong to the second half of the 7th century BC. and were military trophies of the Scythians got during their campaigns in Asia Minor.

The discovery of the treasure happened in fact, at the final stage of the excavations started by Oleksiy Melgunov. The peripheral part of the Lyta Mohyla mound remained intact. Therefore, its research was renewed twice more, at the end of the last century and at the end of the century before the last. Only recently, in 2019, the expedition of the Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine put an end to the study of the famous site.

It turned out that the mound was built not by the Scythians but by their predecessors in these areas. Initially, 700 to 1000 m sq. of oak logs have been brought 12—20 km away from the nearest ravines to compose the basis of the burial structure. A gigantic funeral pyre of some worthy person was made of this pile of logs and other fuel. The precious funeral paraphernalia that accompanied the elite deceased burned and melted. Pieces of the fused clay coating of the funeral construction were often found in this area long since, which was reflected in the name of the mound.

During research in 2019, archaeologists were lucky enough to find two plates made of electrum (a gold and silver alloy), surprisingly preserved in the ancient pyre. Once, these artifacts with ornamentation typical of the cultures of the Hallstatt circle decorated a wooden vessel. They allow us to outline the likely time of construction of the Lyta Mohyla. Only a century, or maybe two, after that, the Scythians, who had just come to these areas, used the mound already existing in this attractive place for a certain religious ceremony.

Old maps explain why the mound is located there. It turns out that the grave was built near the oldest road in Ukraine, which in the Middle Ages was called Black Route. It was built on the site winding through the watershed between the upper reaches of the Ingulets and Ingul rivers. An important ancient Chornolis settlement was located 16 km to the east not accidentally. Ancient Olbia founded near the ford-crossing across Bug liman also owes its location to this ancient highway. However, long before the Greek merchants, the trading caravans of their predecessors from the Dykiy Sad settlement (Mykolaiv City) have travelled to the settlements of the Middle Dnipro this way since the time of the Cimmerians.

Anyway, let us go back from the research of the 21st century to the “research” of the 18th century. The treasure from the Lyta Mohyla changed the fate of the disgraced royal courtier, as well as changed the name of the Site. The mound got its second name — Melgunovsky Kurgan, and Catherine II forgave Oleksiy Melgunov for his former closeness to Peter III.

The finds from the Lyta Mohyla first were transferred to the Kunstkamera in St. Petersburg, and then to the Hermitage in 1859 and 1894. The part of this collection is still kept there. However, some items were returned to Ukraine in 1932 (to the Kharkiv Museum). These artifacts perished during the unsuccessful attempt to evacuate the collections of the Kharkiv Historical Museum to Ufa during the Second World War.

It remains only to note that it would be appropriate to call the stolen treasure Melgunivskyi treasure and to return the usual Ukrainian name of Lyta Mohyla to the burial mound itself.

Boltryk Yurii,

PhD, Head of the Department,

the Institute of Archaeology,

the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

Залізний меч у піхвах із золотими плакуванням. VII ст. до н. е. Місце знахідки: Лита Могила, Наддніпрянщина, Україна.

Місце збереження: музей Державний Ермітаж, Санкт-Петербург, Росія. Інв. № Дн 1763 1/19, 20

Iron sword in a gold-plated scabbard. The 7th c. BC. Place of discovery: Lyta Mohyla, Dnipro Region, Ukraine.

Place of storage: State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Inv. Nr. DN 1763 1/19, 20

|

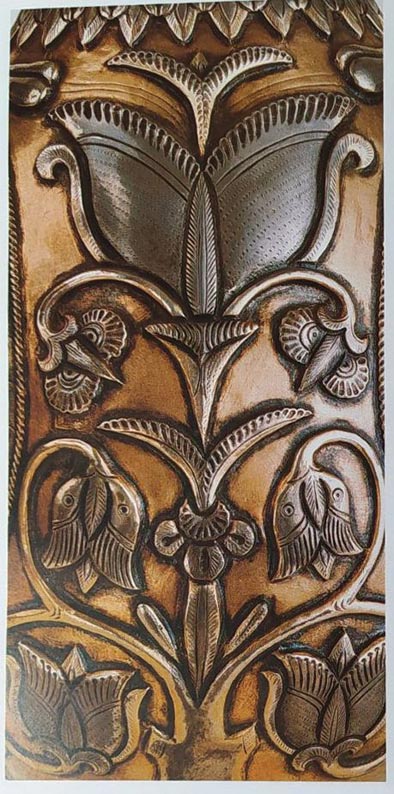

Елементи декору на золотих обкладках піхов. VII ст. до н. е. Лита Могила, Наддніпрянщина, Україна. Місце збереження: музей Державний Ермітаж, Санкт-Петербург, Росія. Decoration elements on the golden plates of the scabbard. The 7th c. BC. Place of discovery: Lyta Mohyla, Dnipro Region, Ukraine. Place of storage: State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Inv. Nr. DN 1763 1/19, 20 |

Діадема. VIII—VII ст. до н. е. Лита Могила, Наддніпрянщина, Україна. Місце збереження: музей Державний Ермітаж, Санкт-Петербург, Росія. Інв. № Дн 1763 1/18

Diadem. The 8th—7th cc. BC. Place of discovery: Lyta Mohyla, Dnipro Region, Ukraine. Place of storage: State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Inv. Nr. DN 1763 1/18

Діадема, деталь. VIII—VII ст. до не. Лита Могила, Наддніпрянщина, Україна. Місце збереження: музей Державний Ермітаж, Санкт-Петербург, Росія

Diadem, fragment. The 8th—7th cc. BC. Place of discovery: Lyta Mohyla, Dnipro Region, Ukraine. Place of storage: State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Орнітоморфна золота платівка. VII ст. до н. е. Місце знахідки: Лита Могила, Наддніпрянщина, Україна. Місце збереження: музей Державний Ермітаж, Санкт-Петербург, Росія.

Інв. № Дн 1763 1/10

Ornithomorphic gold plate. The 7th c. BC. Place of discovery: Lyta Mohyla, Dnipro Region, Ukraine. Place of storage: State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Inv. Nr. DN 1763 1/10

Відновлений насип кургану «Лита Могила» та пам’ятний знак. с. Копані Кропивницький район, Кіровоградська область, Україна

Reconstructed Lyta Mohyla Mound and commemorative sign in Kopani village of Kropyvnythskyi district, Kirovohrad region, Ukraine

5.11.2022

Випуск 4

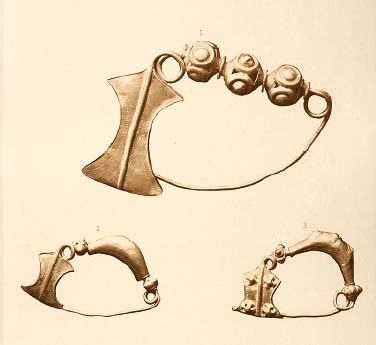

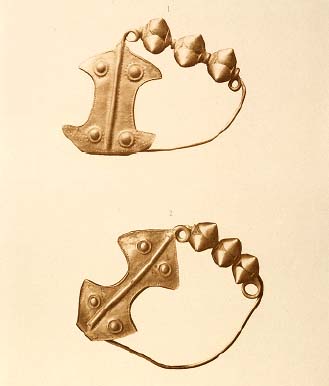

«Кропив’янський» («Полтавський») ритон, напевне чи не перша знахідка, що була віднайдена в Україні та потрапила до російського музею. В колишньому Імператорському, а зараз Державному Ермітажі, в Росії зберігається срібний, з позолотою ритон — посудина для споживання напоїв (чи, можливо, ритуальних узливань), у формі вигнутого рогу, який завершується зображенням передньої частини коня. Знахідку, разом з іншими речами, виявили 1746 р. в межах Кропив’янської сотні Переяславського полку. Відповідно до офіційних документів, її знайшли пастухи в піску, однак є і версія, що ритон походить з поховання у кургані, з якого добували селітру.

Ритон був вивезений російськими можновладцями до Санкт-Петербурга, й потрапив до академічної Кунсткамери. Пізніше знахідка поповнила колекцію імперського Ермітажу, де її зберігають і сьогодні під назвою «Полтавський» ритон. Першу публікацію цієї непересічної знахідки 1916 року зробив знаний український археолог, мистецтвознавець та пам’яткоохоронець Микола Макаренко (1877—1938).

Маса «Кропив’янського» ритону, виготовленого у IV ст. до н. е. найімовірніше у Фракії, складає щонайменше 902 грами.

Детальніше про знахідку: Макаренко, Н. 1916. Материалы по археологии Полтавской губернии. II. Серебряный ритон случайной находки в «Кропивянской сотне Переяславского полку». Труды Полтавской ученой архивной комиссии, вып. 14.

Юрій Пуголовок,

кандидат історичних наук,

заступник Голови правління ВГО “Спілка археологів України”

Release 4

Rhyton of Kropyvna (Poltava) is hardly the first archaeological find that was found in Ukraine and ended up in a Russian museum. The silver gilded rhyton is kept in the former Imperial, and now the State Hermitage Museum in Russia. It is a vessel for drinking made in the form of a curved horn, which ends with a horse’s front part image. The find, along with other items, was discovered in 1746 within the boundaries of the Kropyvna Sotnia of the Pereyaslav regiment. According to official documents, it was found by shepherds in the sand, but there is also a version that the rhyton comes from a burial mound, where saltpetre was mined.

Rhyton was taken by the Russian authorities to St. Petersburg, to the Academic Kunstkamera. Later, the artifact became part of the Imperial Hermitage collection, where it is still kept under the name of the Rhyton of Poltava. The first publication of this extraordinary find was made by Mykola Makarenko, the well-known Ukrainian archaeologist, art critic and heritage conservator (1877—1938).

The mass of the Rhyton of Kropyvna, probably made in Thrace, is more than 902 grams. Archaeologists date the find to the 4th century BC.

Yurii Puholovok,

PhD, deputy chairman of The All-Ukrainian Рublic Association of Archaeologists

|

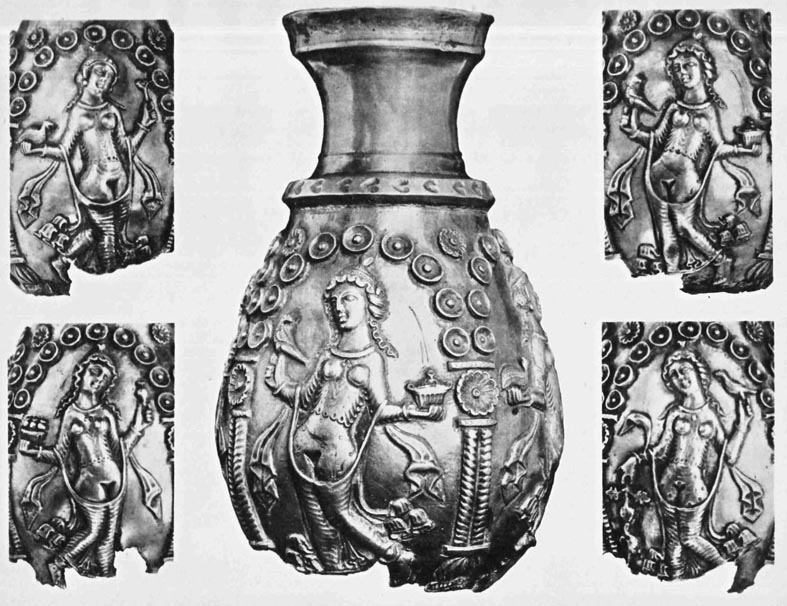

«Кропив’янський» («Полтавський») ритон 4 ст. до н. е., знайдений поблизу містечка Кропивна, 1746 року. Rython of Kropyvna (Poltava), 4th c. BC, found in the surroundings of Kropyvna town, 1746. |

8.11.2022

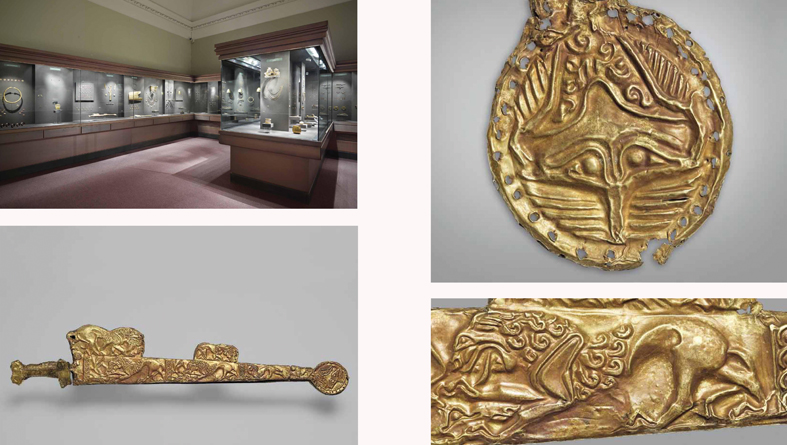

Випуск 5. Справа «скіфського золота» в Амстердамі

Колекція експонатів з «виставки скіфського золота» перебуває в заручниках судової тяганини вже понад 8 років. На відміну від інших історій, про які розповідає кампанія «Археологічна спадщина, вкрадена Росією», ці артефакти поки що не вкрадено. Вони зберігаються у сховищі музею Алларда Пірсона в столиці Нідерландів, доки росія намагається привласнити їх через суд.

Виставку із офіційною назвою «Крим: золото й таємниці Чорного моря» спершу відкрили в Бонні 2013-го, наступного року вона переїхала в Амстердам до музею Алларда Пірсона. Там проєкт тривав з 7 лютого по 31 серпня 2014 року. Неформальну назву — «виставка скіфського золота» — ЗМІ підхопили у 2014-му, хоч насправді не всі предмети — скіфські, й не всі — золоті. До проєкту долучилися 5 інституцій: Національний музей історії України та чотири кримських музеї.

Всі 19 предметів з колекції Історичного музею успішно повернулися до Києва невдовзі по завершенню виставки.

А от доля решти експонатів після анексії півострова склалась інакше. Музей Алларда Пірсона заявив, що кримські експонати залишаються на зберіганні до визначення права власності у судовому порядку. В листопаді 2014 року російська сторона від імені кримських музеїв подала позов із вимогою повернути експонати на півострів, а на початку 2015 у судовий процес вступила держава Україна. Відтоді відбулось декілька судових слухань. Українські представники наполегливо доводять: усі ці речі є об'єктами державної частини Музейного фонду України, а виключне право розпоряджатися своїм культурним надбанням має держава, якій і мають повернути експонати. Російська сторона, формально не беручи участі в процесі, наполягає, аби експонати повернули до кримських музеїв. 26 жовтня 2021 року Апеляційний суд Амстердама ухвалив рішення на користь України. Проте вже у січні 2022 року росія, знову руками кримських музеїв, спробувала оскаржити це у Верховному суді Нідерландів. Нині відомо, що нідерландська юридична фірма відмовилась представляти російську сторону і що позивачі не надали розширені письмові пояснення у відведені терміни. І хоч це дає приводи для оптимізму, впевнитись у ньому можна буде лише після остаточної ухвали Верховного суду Нідерландів, сподіваємось — вже наступного року.

Виставкові матеріали з кримських музеїв налічують 565 предметів. Золоті артефакти та інші знахідки з археологічних комплексів ілюструють минувшину півострова від античності до раннього середньовіччя. Європейські партнери проєкту підготували й опублікували декілька каталогів виставки, надавши їй «постекспозиційного життя».

Познайомимо вас із деякими з експонатів.

Бахчисарайський історико-культурний заповідник надав для європейської виставки 215 предметів страховою вартістю 505700 євро. Серед них — багато матеріалів з некрополів сарматської доби та раннього середньовіччя. Унікальною частиною колекції є 3 китайські лакові шкатулки І ст. н. е. Вони походять з Усть-Альми, що неподалік Бахчисарая, де досліджено один з найбільших і найбагатших некрополів пізньоскіфської культури. Свого часу знахідка стала сенсацією, адже шкатулки подолали неймовірну відстань північною гілкою Шовкового шляху від Китаю до Криму. Скриньки протягом чотирьох років реставрували в Японії. Бахчисарайський заповідник передав і знахідки з інших комплексів — поховальні вінки, сформовані із вирізаних із тонкого золота листочків, прикраси античної доби, унікальні гунські коштовності, тощо.

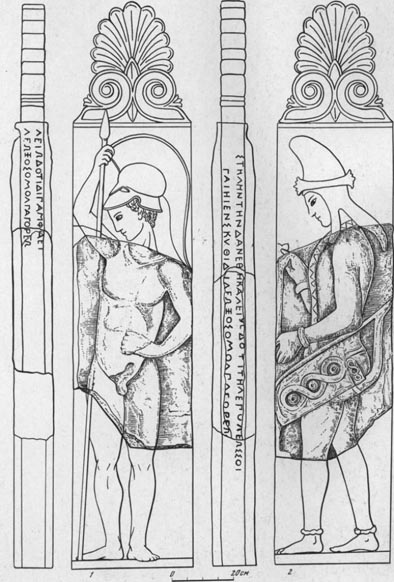

З Керченського історико-культурного заповідника куратори відібрали для виставки 190 предметів страховою вартістю 582000 євро — насамперед, знахідки часів Боспорського царства та його столиці Пантикапея. Звідси до європейських музеїв вирушили античні барельєфи та теракоти, побутові предмети, розписний керамічний посуд, золоті прикраси часів від античності до середньовіччя. Серед них — скульптура «змієногої богині» І—ІІ ст. н. е. заввишки 124 см, що свого часу вважалась візитівкою Керченського заповідника. До пізнішого часу належать зразки спадщини кримських готів, зокрема матеріали першої половини V ст. н. е. з кургану Джург-Оба: сережки, намиста, прикраси з перегородчастою емаллю, тощо.

Національний заповідник «Херсонес Таврійський» передав на виставку 28 предметів страховою вартістю 187000 євро: значну кількість архітектурних деталей, а також епіграфічних пам’яток. Так, на 5 черепках-остраках із Херсонеса можна прочитати імена давніх херсонеситів: «Айгіномос», «Есандрос», «Еварксид, син Зенодота», «Демократеос» та «Евандридос». Серед експонатів представлено й цікавий фрагмент глиняної амфори із написом — частиною юридичного документа — торговельної угоди кінця І — ІІ ст. н. е.

Центральний музей Тавриди представив до експонування 32 предмети страховою вартістю 163925 євро. Серед знахідок — матеріали з досліджень Неаполя Скіфського — столиці Кримської Скіфії, найбільшого і найкраще дослідженого поселення пізньоскіфської культури. На кількох предметах є зображення тамги — родового або особистого знака в кочовиків Євразійського степу, народів Кавказу і Східної Європи. Тамга за часів Кримського ханства стала символом влади, а нині є одним із національних символів Криму. Культура кримських готів представлена знахідками з поховальних комплексів, наприклад — ремінною пряжкою зі срібла й заліза, оздобленою головою орла та інкрустованою склом. Вона походить з могили готської жінки VII ст. н. е., яку археологи дослідили в Лучистому неподалік Алушти.

Знайомство із матеріалами виставки вкотре засвідчує, що мультикультурний «плавильний котел» різних народів — півострів Крим — ніколи не втрачав зв’язків із континентом. Сподіваємось, що переконливі аргументи української сторони у Верховному суді Нідерландів дозволять повернути колекцію державі. Як повернеться і Крим після деокупації, до українських музеїв якого нарешті вирушить колекція «скіфського золота».

Олена Оногда

Кандидатка історичних наук, членкиня ВГО «Спілка археологів України»,

представниця Національного музею історії України у складі делегації Міністерства культури України

на засіданні Окружного суду м. Амстердам (Королівство Нідерланди) за позовом держави Україна

до Амстердамського археологічного Музею Алларда Пірсона (5 жовтня 2016 р.)

Release 5. Case with “Scythian Gold” in Amsterdam

The collection of the “Scythian Gold” Exhibition has been held hostage to court proceedings for more than eight years. Unlike other cases described in the framework of the Archaeological Heritage Stolen by Russia Campaign, these artifacts have not yet been stolen. They are kept in the Allard Pearson Museum in the Dutch capital, while Russia tries to appropriate them through the courts.

The exhibition, officially named “Crimea: Gold and Mysteries of the Black Sea”, was first opened in Bonn in 2013. The following year it moved to Amsterdam to the Allard Pearson Museum. There, the project lasted from February 7 to August 31, 2014. Its informal name — “Scythian Gold Exhibition” — was picked up by the mass media in 2014, although, actually, not all exhibited objects are Scythian, and not all of them are gold. Five institutions joined the project: the National Museum of the History of Ukraine and four Crimean museums.

All 19 items from the collection of the Historical Museum successfully returned to Kyiv shortly after the exhibition ended.

However, the fate of the rest of the exhibits was different after the annexation of the peninsula. The Allard Pearson Museum stated that the Crimean exhibits should remain in storage until ownership is determined in court.

In November 2014, the Russian side filed a lawsuit on behalf of the Crimean museums demanding the return of the exhibits to the peninsula, and in early 2015, the state of Ukraine joined the legal process. Since then, several court hearings have taken place. Ukrainian representatives persistently prove that all these artifacts belong to the state part of the Museum Fund of Ukraine. These exhibits should be returned to the State which has the exclusive right to dispose of its cultural property. The Russian side, nominally not participating in the process, insists that the exhibits should be returned to the Crimean museums. On October 26, 2021, the Amsterdam Court of Appeals ruled in favour of Ukraine. However, already in January 2022, Russia tried to challenge this in the Supreme Court of the Netherlands, again using Crimean museums. It is known that the Dutch law firm refused to represent the Russian side and that the plaintiffs did not provide extended written explanations within the allotted time. Although this gives reasons for optimism, only after the final decision of the Supreme Court of the Netherlands will it be possible to make sure of it, hopefully — already next year.

Exhibition materials from Crimean museums number 565 items. Gold artifacts and other finds from archaeological sites illustrate the past of the peninsula from antiquity to the early Middle Ages. European partners of the project prepared and published several catalogues of the exhibition, giving it a “post-expositional life”.

We will introduce you to some of the exhibits.

The Bakhchysarai Historical and Cultural Preserve provided 215 items for a total insurance value of 505700,00 Euros for the European exhibition. Different materials from the necropolises of the Sarmatian era and the early Middle Ages are among them. Three unique Chinese lacquer boxes from the 1st century AD are part of the collection. They come from Ust-Alma, near Bakhchysarai town, where one of the largest and richest necropolises of the late Scythian culture was investigated. At the time, the discovery became a sensation, because the boxes had travelled an incredible distance along the northern branch of the Silk Road from China to Crimea. They were in restoration in Japan for four years. The Bakhchysarai Preserve also provided archaeological finds from other complexes — funeral wreaths made of leaves cut from thin gold, antique jewellery, unique Hun jewels, etc.

The curators selected for the Exhibition 190 items from the collection of the Kerch Historical and Cultural Preserve, for a total insurance value of 582 000,00 Euros. First of all, these were finds of the Bosporus Kingdom time and its capital Panticapaeia. Ancient bas-reliefs and terracottas, household items, painted ceramic ware, and gold jewellery from antiquity to the Middle Ages went to European museums. Among them is a Snake-Legged Goddess statuette of the 1st—2nd century AD with a height of 124 cm, which at one time was considered a visiting card of the Kerch Preserve. Samples of the Crimean Goths’ heritage belong to later times, in particular materials from the first half of the 5th century AD from the Jurg-Oba burial mound: earrings, necklaces, ornaments with partitioned enamel, etc.

The National Preserve “Tauric Chersonese” handed over 28 objects for a total insurance value of 187000,00 Euros for the exhibition: a significant number of architectural details, as well as epigraphic monuments. Among them are five ostracas (pieces of pottery) from Chersonese containing written names of the ancient Chersonesites: “Ayginomos”, “Esandros”, “Evarxis, son of Zenodotus”, “Demokratheos” and “Evandridos”. Among the exhibits is an interesting piece of a clay amphora with an inscription — a fragment of a legal document — a trade agreement dated the late 1st — 2nd century AD.

The Central Museum of Tavrida handed over 32 items to exhibit for a total insurance value of 163925,00 Euros. Among the finds are materials from the investigation of Naples of Scythia — the capital of Crimean Scythia, the largest and best-researched hill-fort of Late Scythian culture. Several items contain an image of tamga — a family or a personal sign of the Eurasian steppe nomads, the peoples of the Caucasus and Eastern Europe. During the time of the Crimean Khanate, the tamga became a symbol of power, and today it is one of the national symbols of Crimea. The Crimean Goths’ culture is represented by finds from burial complexes, for example, a belt buckle made of silver and iron, decorated with an eagle's head and inlaid glass. It was found in the grave of a Gothic woman of the 7th century AD, investigated by archaeologists in Luchyste village near Alushta.

Archaeological materials of the exhibition prove once again that the Crimean peninsula being a multicultural “melting pot” of different peoples, has never lost its ties with the continent. We hope that the convincing arguments of the Ukrainian side in the Supreme Court of the Netherlands will foster the return of the collection to the State. Just as Crimea will return after de-occupation, the Scythian Gold collection will finally come back to its Ukrainian museums.

Olena Onohda

PhD in history, member of the Ukrainian Association of Archaeologists,

representative of the National Museum of the History of Ukraine to the delegation of the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine

at the session of the District Court of Amsterdam (Kingdom of the Netherlands) on the claim of the State of Ukraine

against the Allard Pearson Museum of Antiquities in Amsterdam (October 5, 2016)

Сережки з поховання ІІ ст. до н. е. — кінця IV ст. н. е. Усть-Альмінський некрополь. Колекція Бахчисарайського історико-культурного заповідника

Earrings from a burial of the 2nd century BC — the end of the 4th century AD. Ust-Alminsky necropolis. Collection of the Bakhchisarai Historical and Cultural Preserve

Пряжка. VII ст. н. е. Колекція Центрального музею Тавриди

Buckle. 7th century AD. Collection of the Central Museum of Tavrida

Китайська лакова шкатулка. І ст. н. е. Усть-Альмінський некрополь. Колекція Бахчисарайського історико-культурного заповідника

Chinese lacquer box. 1st century AD. Ust-Alminskyi necropolis. Collection of the Bakhchysarai Historical and Cultural Preserve

Скульптура «змієногої богині». І—ІІ ст. н. е. Колекція Керченського історико-культурного заповідника

Statuette of a Snake-Legged Goddess. 1st—2nd century AD. Collection of the Kerch Historical and Cultural Preserve

Остраки з Херсонеса. Колекція Національного заповідника «Херсонес Таврійський»

Ostracas (pieces of pottery) from Chersonesus. Collection of the National Preserve “Tauric Chersonese”

Source of illustrations: Die Krim: Goldene Insel im Schwarzen Meer: Griechen—Skythen—Goten. Bonn: LVR-LandesMuseum, 2014

20.11.2022

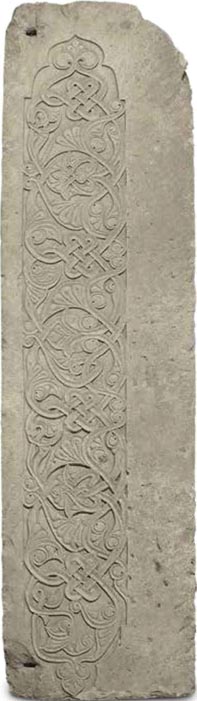

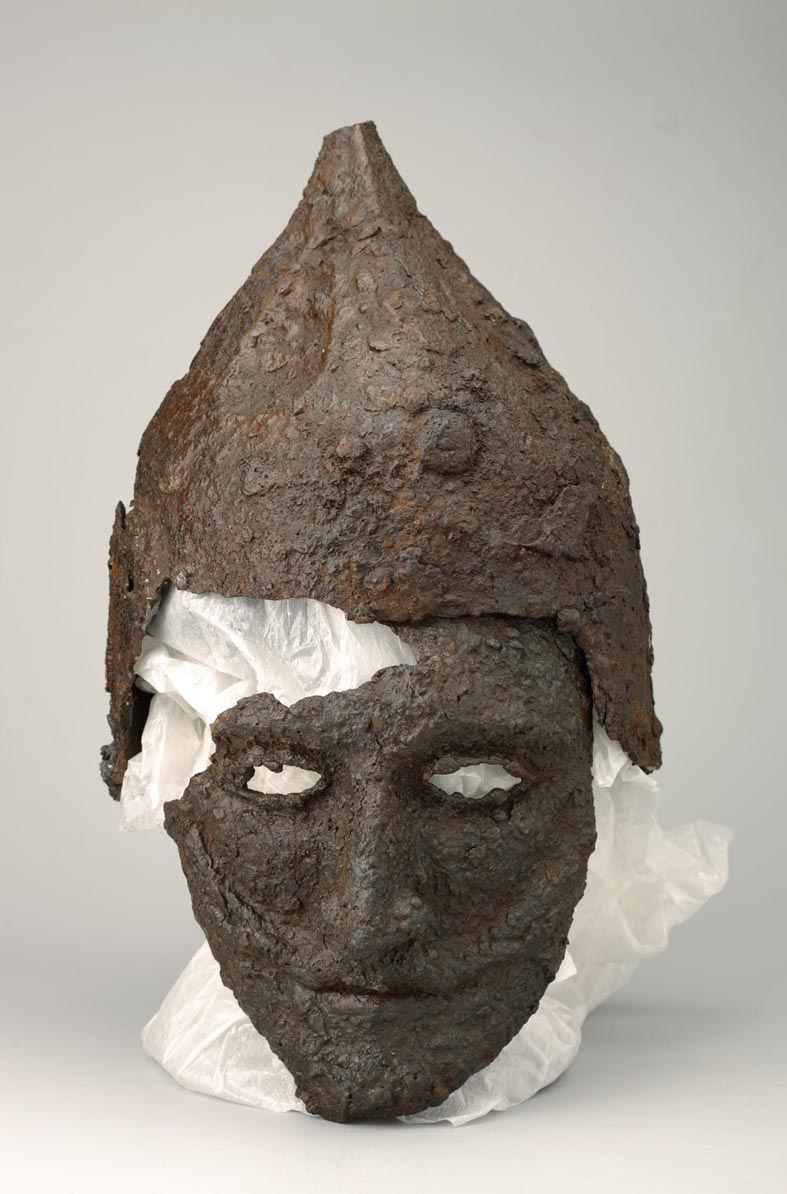

Випуск 6. Кам’яне мереживо. Вкрадене з Солхату

Історія грабунку кримських пам’яток Ермітажем сягає майже двохсот років: на території півострова працювала безліч археологічних експедицій з Санкт-Петербургу. Одна з найстаріших, що діє й тепер, — Старокримська археологічна експедиція державного Ермітажу. Тож не дивно що більшість знахідок, які походять із Солхату (середньовічне місто XIII—XV ст., що було столицею Кримського Юрту, тепер має назву Старий Крим), вивезені з Криму до Росії за сприяння імперських науковців.

Одним із найпоширеніших типів археологічних предметів з Солхату, привласнених Санкт-Петербургом, є різноманітні архітектурні елементи: різьбленні фрагменти споруд, надгробки, капітелі. Точна кількість знахідок, поцуплених з середньовічного Солхату, невідома. Знакові й найважливіші для репрезентації безперервного розвитку традицій місцевого населення є артефакти, якими росіяни хизувалися 2019 року на виставці «Золота Орда і Причорномор’я. Уроки Чингизидської імперії» в Казані.

Замкóвий камінь, за припущенням керівника експедиції Ермітажу в Старому Криму — Марка Крамаровського, був частиною арки медресе Солхату — найдавнішого мусульманського релігійно-просвітницького закладу на території півострова, побудованого в 1332—1332 роках коштом меценатки Інджи-Бек-Хатун. Залишки автентичного архітектурного оздоблення медресе майже не збереглися до часу археологічних досліджень, і камінь, виявлений під час розкопок наприкінці 1980-х років, є чи не єдиним свідченням запозичень з архітектури Румського султанату (Мала Азія), що розпався за два десятиліття до будівництва медресе.

Інший замкóвий камінь, віднайдений під час розкопок 1987/1990 років, походить з мавзолею кінця XІV — початку XV століття. На камені закарбовано ім’я Махмуда ібн Османа аль-Ірбілі, остання частина якого (нісба) вказує на походження архітектора з міста Ірбіль (Ербіль) в сучасному Іраку. Цікаво, що імовірний зодчий мечеті Узбека (1314 р.) — Абдул-Азіз аль-Ірбілі, судячи з нісби, також походив з давнього міста в Месопотамії, що пояснює ранні прояви сельджукської архітектури в Криму.

Якщо переміщення попередніх двох архітектурних елементів із Солхата в Санкт-Петербург вкладається в логіку радянської музейної системи, то привласнення Ермітажем різьбленого блоку, імовірно з облицювання порталу медресе першої чверті XIV століття, нагадує кримінальні хроніки. Під час розкопок кургану Кємаль-Ата в 1994—1996 роках дослідили чоловіче поховання, яке частина дослідників пов’язує із Мамаєм, перекрите двома плитами, покладеними на ребро. Однією з цих плит і була повторно використана плита з облицювання медресе. Цей різьблений камінь із малоазійським орнаментом 2018 року, вже після окупації Криму, «поступив» зі Старокримської археологічної експедиції до Ермітажу. Протягом 24 років один з небагатьох архітектурних елементів першої медресе в Солхаті не передавали до музейних колекцій, а «зберігали», що вчергове ілюструє «російську турботу» про культурну спадщину захоплених територій.

Вже згадану виставку «Золота Орда і Причорномор’я. Уроки Чингизидської імперії» без перебільшень можна назвати квінтесенцією колоніальної політики — презентацією привласненої культурної спадщини поневолених народів. Замкóві камені з медресе Солхату та мавзолею XV століття, різьблений блок з облицювання порталу медресе, капітелі — це не просто архітектурні елементи, а ілюстрація культурних зв’язків середньовічного Солхату із Месопотамією, Золотою Ордою, Анатолією (сучасна Туреччина). Тож вилучення таких предметів з території їх походження, вириває історію Криму з європейського та азійського контекстів. Натомість утворюється все більше місця для міфу про «російський Крим», який старанно поширюють для широкого загалу.

Яшний Денис,

кандидат історичних наук, провідний науковий співробітник Національного заповідника "Києво-Печерська лавра",

аналітик ГО "Кримський інститут стратегічних досліджень"

Release 6. Stone lace. Stolen from Solkhat

The history of looting Crimean monuments by the Hermitage goes back almost two hundred years: many archaeological expeditions from St. Petersburg worked on the peninsula. One of the oldest, still active, is the Staryi Krym Archaeological Expedition of the State Hermitage. Therefore, it is not surprising that most of the finds originating from Solkhat (a medieval city of the 13th—15th centuries, which was the capital of the Crimean Yurt, now called Staryi Krym) were taken from the Crimea to Russia with the assistance of imperial scientists.

Among the most common types of archaeological artifacts from Solkhat, appropriated by St. Petersburg, are various architectural elements: carved fragments of buildings, tombstones, capitals. The exact number of discoveries nicked from medieval Solkhat is unknown. The artifacts that Russians flaunted in 2019 at the exhibition “The Golden Horde and the Black Sea Region. Lessons of the Chingizid Empire” in Kazan are the most iconic and important for the representation of the continuous development of the local traditions.

According to Mark Kramarovsky, the Head of the Hermitage expedition in the Staryi Krym, the keystone was part of the arch of the Solkhat madrasa, the oldest Muslim religious and educational institution on the territory of the peninsula, constructed in 1332—1332 at the expense of the patroness Inji-Bek-Hatun.

The authentic architectural decoration of the madrasa was almost not preserved until the time of archaeological research, and the keystone discovered during excavations in the late 1980s is hardly the only evidence of borrowings from the architecture of the Rum Sultanate (Asia Minor), which fell apart two decades before the construction of the madrasa.

Another keystone, found during excavations in 1987/1990, comes from a mausoleum of the late 14th — early 15th century. The name of Mahmud ibn Osman al-Irbili is engraved on the stone. The last part of his name (nisba) indicates the origin of the architect from the city of Irbil (Erbil) in modern Iraq. It is interesting that the alleged architect of the Uzbek mosque (1314), Abdul-Aziz al-Irbili, judging by the nisba, also came from an ancient city in Mesopotamia, which explains the early manifestations of Seljuk architecture in the Crimea.

If the transfer of the previous two architectural elements from Solkhat to St. Petersburg fits into the logic of the Soviet museum system, then the appropriation by the Hermitage of a carved block, presumably from the cladding of the portal of a madrasa dated the first quarter of the 14th century, reminds criminal chronicles. During the excavations of the Kemal-Ata burial mound in 1994—1996, a male burial that some researchers associate with Mamai was investigated. Two slabs placed on the edge covered the burial. One of them was a reused slab from the madrasa cladding. In 2018, already after the occupation of Crimea, this carved stone with Asia Minor ornament “came” to the Hermitage from the Staryi Krym Archaeological Expedition. For 24 years, one of the few architectural elements of the first madrasa in Solkhat was not transferred to museum collections, but “preserved”, which once again illustrates “Russian care” for the cultural heritage of the occupied territories.

The already mentioned exhibition “The Golden Horde and the Black Sea Region. Lessons of the Chingizid Empire” without exaggeration can be called the quintessence of colonial policy — a presentation of the cultural heritage appropriated from enslaved peoples. Keystones from the Solkhat madrasa and mausoleum of the 15th century, a carved block from the cladding of the madrasa portal, and capitals are not just architectural elements, but an illustration of the cultural ties between medieval Solkhat and Mesopotamia, the Golden Horde, and Anatolia (modern Turkey). Therefore, the removal of such artifacts from the territory of their origin cut out the history of Crimea from the European and Asian contexts. Instead, the myth of “Russian Crimea” takes up more and more space, being diligently disseminated to the public.

Denys Yashnyi,

PhD, research fellow of National Preserve "Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra",

analist of the NGO "Crimean institute of strategic studies"

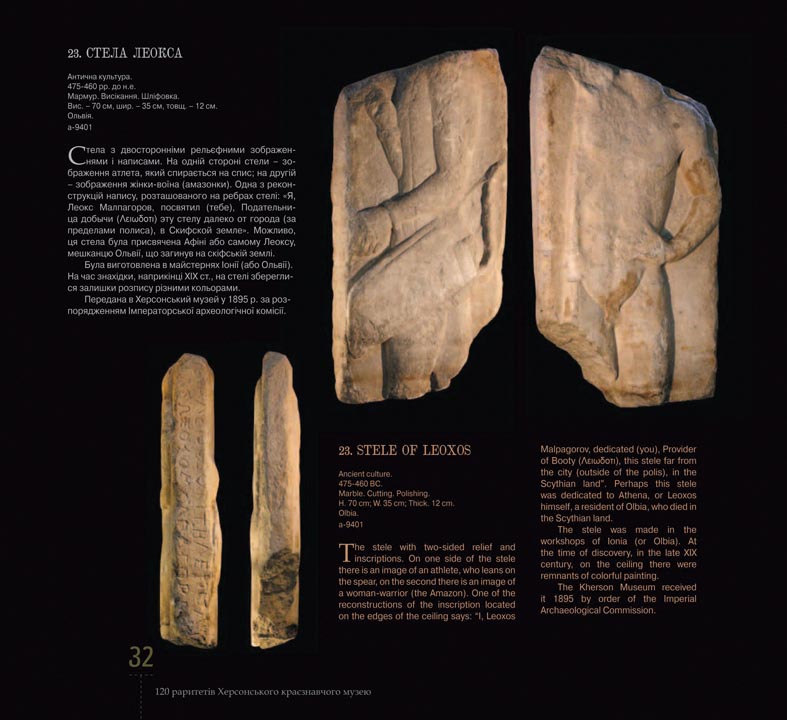

Замкóвий камінь. Золота Орда. Крим. Солхат. З розкопок мавзолею кінця XІV —

початку XV ст. (1987/1990 рр.) «Державний Ермітаж» інв. № Сол-157

Keystone. Golden Horde. Crimea. Solkhat. From the excavations of the mausoleum of the late 14th —

early 15th (1987/1990) State Hermitage inv. Nr. Sol-157

Замкóвий камінь з ім’ям Османа. Золота Орда. Крим. Солхат. З розкопок медресе XІV ст. (1980-і рр.) «Державний Ермітаж» інв. № Сол-156

Keystone with engraved name of Osman. Golden Horde. Crimea. Solkhat. From the excavations of the madrasa of the 14th century (the 1980s)

State Hermitage inv. Nr. Sol-156

Різний блок. Золота Орда. Крим. Солхат. З розкопок кургану Кемаль-Ата (1994—1996 рр.)

«Державний Ермітаж» інв. № Сол-168

Carved stone block. Golden Horde. Crimea. Solkhat. From the excavations of the Kemal-Ata burial mound

(1994—1996) State Hermitage inv. Nr. Sol-168

Source of illustrations:

Золотая Орда и Причерноморье: уроки Чингисидской империи: каталог выставки, [2 апреля — 6 октября 2019 г., Казань] / авт. вступ. ст. М. Г. Крамаровский.

Golden Horde and Black Sea Region: Lessons of Chingizid Empire: exhibition catalogue, [April 2 — October 6, 2019, Kazan] / Mark Kramarovsky, author of the introductory article

25.11.2022

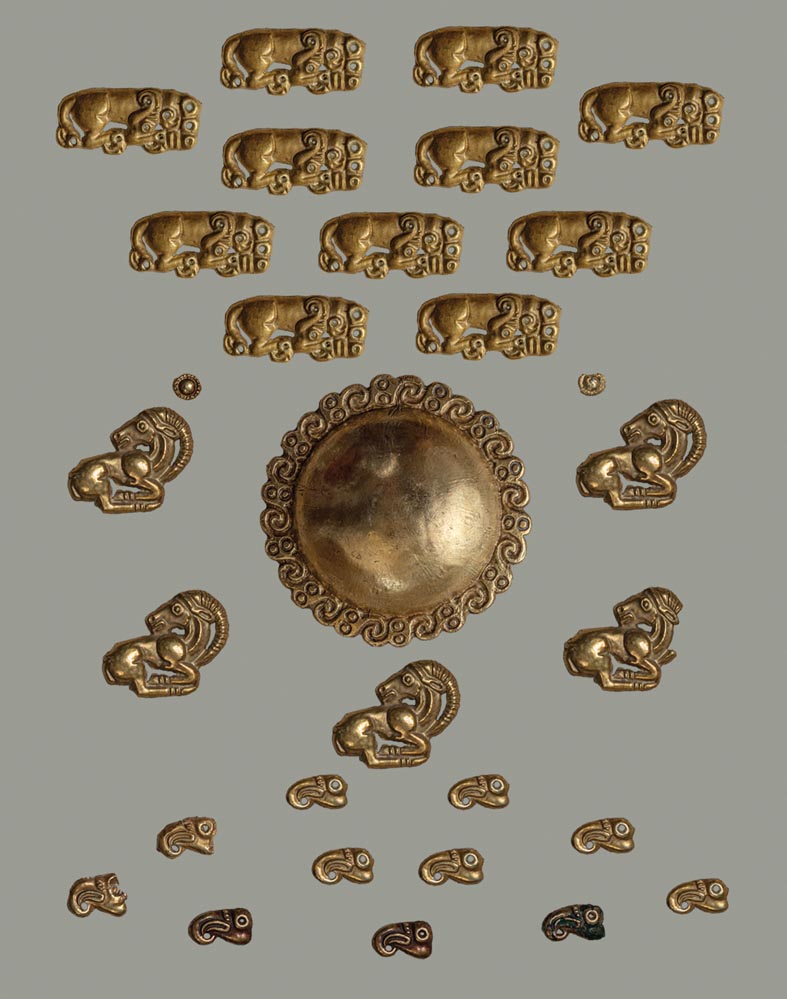

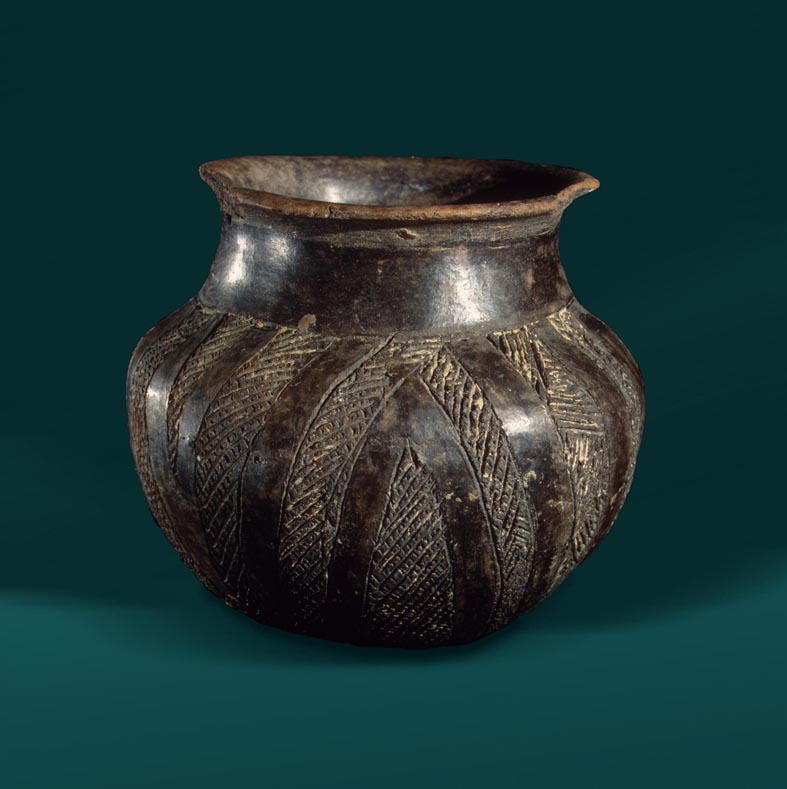

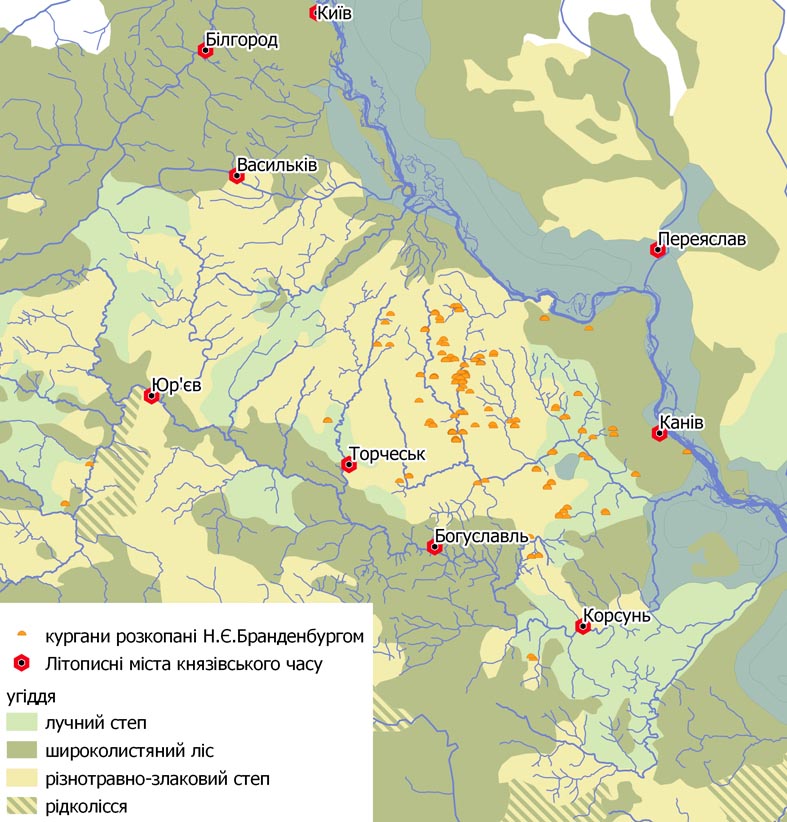

Випуск 7. Вітова могила

У 1888 році український археолог Іван Зарецький дослідив курган Вітова могила, неподалік Опішні, в долині р. Мерла, де виявив багате воїнське поховання рубежу VI—V ст. до н. е. Земляний насип цієї поховальної споруди вирізнявся розмірами на тлі інших курганів в околиці. Поховання супроводжувалося значною кількістю інвентарю, що вказувало на високий соціальний статус похованого.

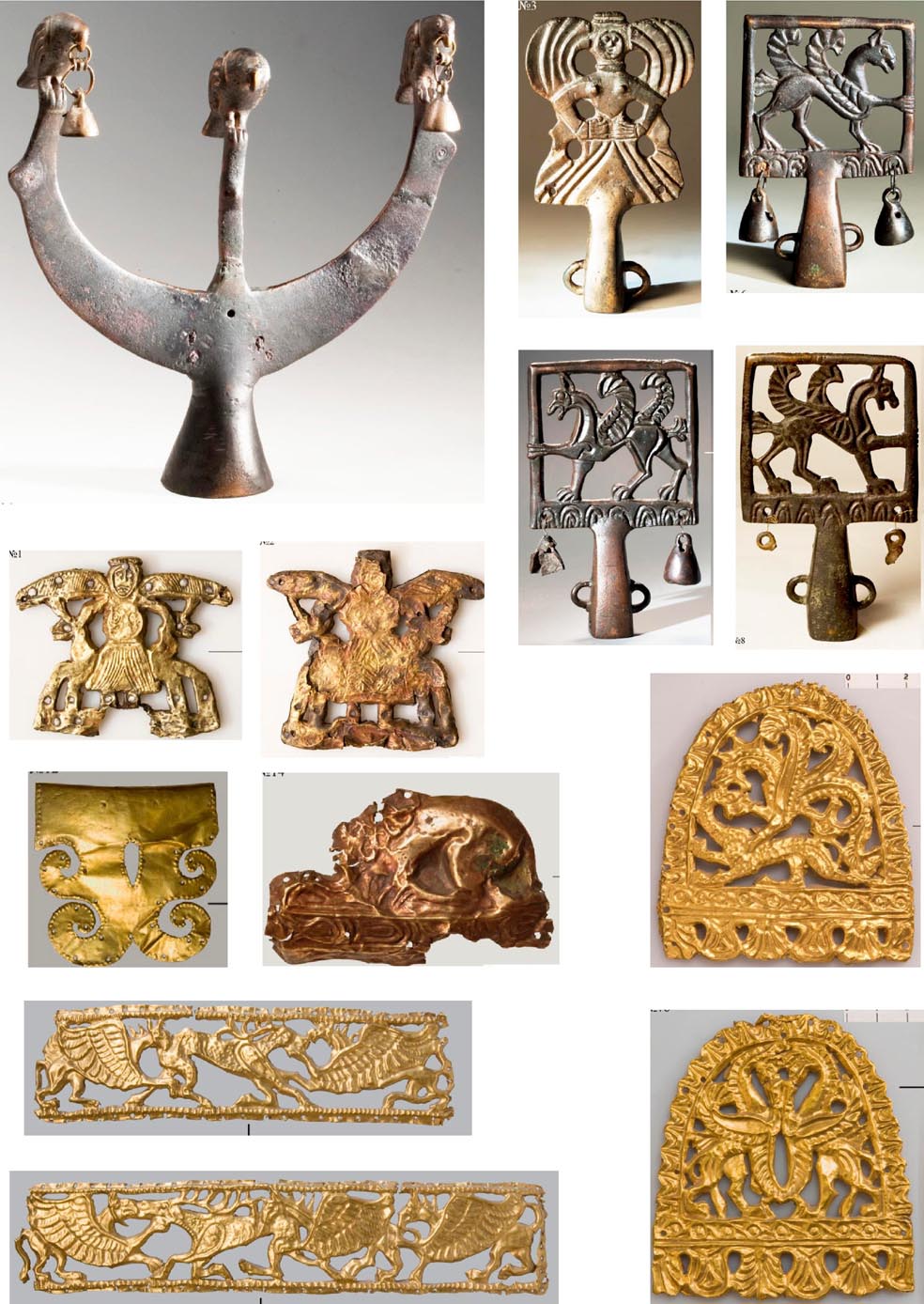

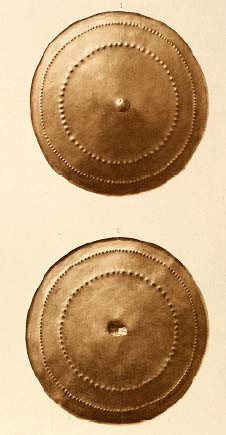

Серед знахідок — предмети озброєння, у тому числі сагайдак з берести, обтягнутий хутром й прикрашений композицією із золотих бляшок, виконаних у скіфському звіриному стилі. Центральне місце посідала велика кругла опукла бронзова бляха, вкрита золотом. По верхньому краю сагайдака були нашиті одинадцять золотих бляшок у вигляді фігурок пантер з петельками на обороті, по низу — шість золотих бляшок у вигляді фігурок гірських козлів у галопі, з повернутими назад головами. По краю напівкруглого дна сагайдака містилося одинадцять золотих бляшок у вигляді орлиних головок із загнутим дзьобом, а чотири його кута оздобили маленькими круглими опуклими золотими бляшками-розетками. У сагайдаку виявили понад 200 бронзових наконечників стріл. У похованні також зафіксували деталі кінської вузди та інші предмети.

Проведені Іваном Зарецьким розкопки повністю вичерпали його фінансові ресурси та підірвали дослідницькі прагнення науковця. Він вдався до пошуку додаткових грошей деінде. Скориставшись скрутою українського вченого, Московське археологічне товариство нав’язало Іванові Зарецькому кредит, умовою погашення якого стало придбання Російським історичним музеєм у Москві звіту та всієї колекції знахідок майже за безцінь. У підсумку, речі з його розкопок й досі зберігаються у Державному історичному музеї, а документація розпрошена по різними архівним установам Росії.

Юрій Пуголовок,

кандидат історичних наук, заступник Голови правління ВГО “Спілка археологів України”

Release 7. Vitova Mohyla

In 1888, the Ukrainian archaeologist Ivan Zaretsky investigated the burial mound of Vitova Mohyla, located near Opishna, in the valley of the Merla River. A rich military burial dated around the turn of the 6th—5th century BC was discovered in it. The dimensions of the earthen mound of this burial structure distinguish it from other mounds in the vicinity. The burial contained a significant number of inventory, which indicated the high social status of the buried person.

Among the finds were weapons, including a saadak (quiver) made of birch bark and covered with fur. It was decorated with gold plaques composition made in the Scythian animalistic style. A large round convex bronze plate covered with gold was placed at the center. On the upper edge of the quiver were sewn eleven gold plaques in the form of figures of panthers with hooks on the reverse. Six gold plaques in the form of figures of mountain goats in a gallop, with their heads, turned back were sewn on the bottom. Along the edge of the semicircular bottom of the quiver were placed eleven gold plaques in the form of eagle heads with bent beaks, and at its four corners were small round convex gold rosette plaques. More than 200 bronze arrowheads were found in the quiver. Fragments of a horse bridle and other items were also discovered in the burial.

The excavations conducted by Ivan Zaretsky completely exhausted his financial resources and undermined the scientist's research aspirations. He tried to search for additional funding elsewhere. Taking advantage of the Ukrainian scientist's predicament, the Moscow Archaeological Society imposed a loan on Ivan Zaretsky. The loan terms were the purchase of the report and the entire collection of finds by the Russian Historical Museum in Moscow for almost nothing. As a result, artifacts from his excavations are still kept in the State Historical Museum, and the documentation is scattered among various Russian archival institutions.

Yurii Puholovok,

PhD, deputy chairman of The All-Ukrainian Рublic Association of Archaeologists

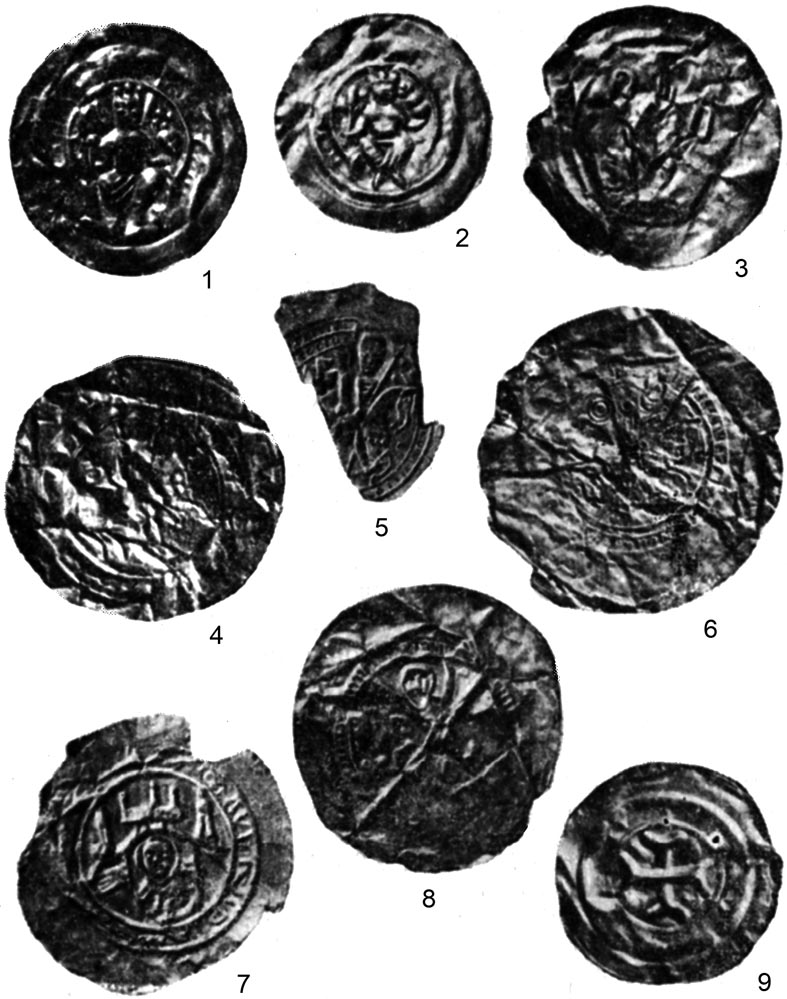

Знахідки з кургану Вітова могила, VI—V ст. до н .е. Зберігаються у Державному історичному музеї, Москва, Росія

Archaeological finds from the Vitova Mohyla burial mound, 6th—5th century BC. Stored in the State Historical Museum, Moscow, Russia

27.11.2022

Випуск 8. Радянська влада і грабунок культурної спадщини Кочубеїв у Диканьці

Селище Диканька (тепер Полтавський район Полтавської області) відоме чи не на весь світ завдяки твору Миколи Гоголя. Окрасою Диканьки був маєток знаного та заможного козацько-дворянського роду Кочубеїв. Від кінця XVII століття цей маєток був місцем акумулювання різноманітних історико-культурних цінностей меморіального та мистецького характеру. У XІХ столітті колекції збагатилися і археологічними знахідками, оскільки власники активно долучилися до збирання та дослідження пам’яток давніх епох. Як свідчив у спогадах директор Полтавського музею Валентин Ніколаєв, котрий бачив приголомшуючі артефакти, що залишилися після від’їзду власників за кордон 1918 року, «приміщення палацу було буквально набите в окремих кімнатах картинами, старовинною бронзою, килимами, гобеленами, цінним фаянсом, фарфором і склом, старовинною зброєю і т. д. Величезну цінність мала прекрасна бібліотека…».

Зауважимо, що освічені жителі Диканьки, яких у селищі було чимало, та службовці місцевої економії не дозволили грабунку кочубеївської власності в 1917—1918 роках. Колегія з управління маєтками, до складу якої увійшли і представники від селянства, ретельно охороняла залишене Кочубеями майно. «А ні прутика, а ні гвинтика селяне не зачепили» Все уціліло, окрім кількох пістолетів та шабель. Працювала навіть палацова електростанція.

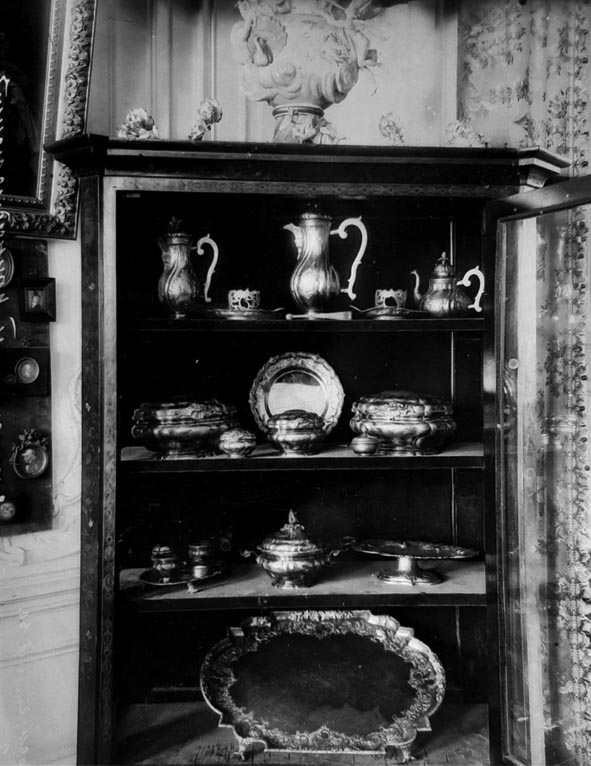

Але більшовицькі зайди не могли залишити таких багатств Україні. Спочатку навесні 1918 року «Перша совітська бригада або 8 полк» перевіз до Полтави три скрині срібних виробів (близько 480 кілограм, 670 предметів), які згодом відправили до Москви, й цінні артефакти зникли безслідно. Очевидно, що реквізиція відбувалася насильницьким шляхом. Відповідно, коли за «других совітів» (квітень 1919 року) до палацу з метою опису предметів старовини та відбору експонатів для Полтавського музею приїхали його співробітники археолог Михайло Рудинський і природознавець-пам’яткознавець Валентин Ніколаєв, їх хоч і допустили до колекцій, але тривалий час не погоджувалися на вивіз відібраних старожитностей і навіть погрожували вчинити самосуд над приїжджими. Місцеві селяни та службовці економії стверджували, що будь-яке вилучення є незаконним, адже «князь їм говорив, що рано чи пізно все його майно повинно відійти селянам і вони мають турбуватися про його охорону». Лише коли полтавські музейники посприяли створенню музею Диканьки в кількох кімнатах першого поверху палацу, диканці дозволили і допомогли вивезти найцінніші картини, ікони, зразки посуду, бронзи, зброї, книг, родинний архів. Почасти ці предмети й донині залишаються в Україні, але чимала їх частина зрештою була вивезена до РФ.

Певний час після приїзду полтавців новостворений диканський музей та пивоварний завод, як згадував активних учасник тих подій Яків Орисенко, охороняли «добровольці і слабі старики Диканського загону Авраменка М.». Але через підпал палац з висококоштовними речами перетворився на руїни. Існує кілька версій щодо того, хто зробив цей злочин. Найпоширенішу версію озвучив у спогадах Валентин Ніколаєв. Суть її така — осіннього дня з лісу виїхав загін озброєних вершників і став табором навколо палацу. Потім ці вершники сіли на коней, а через годину палац запалав. Диканці називали цих людей партизанами, а Валентин Ніколаєв уточнив, що це була «шайка грабіжників, що називали себе народними партизанами, котрі не тільки розтягнули ряд предметів, а й спалили весь палац і службові приміщення. Багато книг було кинуто в став».

Зі спогадів безпосереднього учасника цих подій, мешканця Решетилівки Прохора Білоконя, відомо, що вандали входили до загону Якова Огія (уродженця Кобеляцького повіту, члена УПСР (боротьбисти)). Незадовго перед подіями в Диканьці цей загін отримав директиву від членів Зафронтового бюро, підпорядкованого Центральному комітету Комуністичної партії більшовиків України, діючи в тилах денікінців дискредитувати їх, зривати мобілізацію, руйнувати мости та зв’язок. Уранці 13 жовтня цей загін, озлоблений після поразки під Полтавою, як писав один із його бійців Прохор Білокінь, «погромивши пивний завод, електростанцію, мельницю… спалив і дворець двоповерховий в 105 комнат». Таким чином, все що більшовики не вивезли з Диканьки, було за їхніми настановами спалено безповоротно.

Останній акт вандалізму, зумовлений відповідною політикою московського уряду, стався вже щодо останків Кочубеїв, в тому числі одного з перших в російській імперії археологів-нумізматів Василя Вікторовича. У 1932—1933 роках диканськими «активістами» було розкрито саркофаги в склепі Миколаївської церкви і забрано звідти вироби з дорогоцінних металів.

Описи пограбування та плюндрування палацу Кочубеїв століття тому напрочуд нагадують поточні новини з тимчасово окупованих територій нашої держави. Викрадення та вивезення музейних колекцій, бездумне винищення всього, що вивезти не вдалося. За сто років нічого не змінилося в «методах» ставлення до українського культурного спадку з боку східних зайд.

Анатолій Щербань,

доктор культурології, завідувач кафедри історії, музеєзнавства та пам'яткознавства Харківської державної академії культури

Release 8. Soviet government and the looting of the Kochubeys Family’s cultural property in Dykanka

The village of Dykanka (nowadays the Poltava district of the Poltava region) is known almost all over the world thanks to the work of Mykola Gogol. The estate of the well-known and wealthy Cossack-noble Kochubeys family was the decoration of Dykanka. Since the end of the 17th century, this estate has been a place of accumulation of various historical and cultural values of memorial and artistic importance. In the 19th century, the owners actively participated in collecting artworks and researching the sites of ancient eras and enriched their collections with archaeological finds. Valentyn Nikolaiev, the director of the Poltava Museum, described in his memoirs stunning artifacts that remained in the estate after the departure of the owners abroad in 1918: “a number of rooms in the palace were literally stuffed with paintings, ancient bronzes, carpets, tapestries, valuable faience, porcelain and glass, ancient weapons, etc. A wonderful library was of great value...”.

It should be noted that educated inhabitants of Dykanka, of whom there were many in the village, and employees of the local economy did not allow the looting of Kochubeys property in 1917—1918. The estate management board, which included representatives from the peasantry, carefully guarded the property left by the Kochubeys. “The peasants didn't touch a stick or a cog”. Everything survived, except for a few pistols and sabres. Even the palace power station was running.

Nevertheless, the Bolshevik invaders could not leave such treasures in Ukraine. First, in the spring of 1918, the “First Soviet Brigade or 8th Regiment” transported three boxes of silverware (670 items weighing about 480 kilograms,) to Poltava. Later, the valuable artifacts were sent to Moscow and disappeared without a trace. It is obvious that the requisition was carried out by force. Accordingly, during the “second Soviet period” (April 1919) the employees of the Poltava Museum, the archaeologist Mykhailo Rudynskyi and the naturalist and heritage expert Valentyn Nikolaiev, came to the palace to describe antiquities and select exhibits for the Museum. Although they were admitted to the collections, for a long time they did not agree to the removal of the selected antiquities and even threatened to lynch newcomers. Local peasants and economy officials claimed that any seizure was illegal, because “the prince told them that sooner or later all his property should go to the peasants so they should care about its protection”. Only when the Poltava museum workers contributed to the creation of the Dykanka Museum in several rooms on the ground floor of the palace, the Dykanka’s inhabitants allowed and helped to take out the most valuable paintings, icons, samples of dishes, bronzes, weapons, books, and the family archive. Some of these items remain in Ukraine to this day, but a significant part of them was eventually exported to the Russian Federation.

As recounted by Yakiv Orysenko, an active participant in those events, some time after the arrival of the Poltava citizens, the newly created Dykanka museum and brewery were guarded by “volunteers and weak old men of the Dykanka detachment led by M. Avramenko”. Due to arson, the palace with valuable things turned into ruins. There are several versions of who committed this crime. The most widespread version was mentioned by Valentyn Nikolaiev in his memoirs. On an autumn day, a detachment of armed horsemen left the forest and camped around the palace. Then these riders got on their horses, and an hour later the palace caught fire. The villagers called these people partisans, and Valentyn Nikolaiev clarified that it was “a gang of robbers, who called themselves national partisans. They not only looted a number of items, but also burned the entire palace and service premises. Many books were thrown into the pond”.

From the memories of Prokhor Bilokin, a resident of Reshetylivka and the immediate participant in the events, it is known that the vandals were from the detachment of Yakiv Ohii (a native of Kobelyatsky district, a member of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries). Shortly before the events in Dykanka, this detachment received a directive from the members of the Front Office, subordinate to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Bolsheviks of Ukraine, to act in the rear of the Denikinites in order to discredit them, disrupt mobilization, destroy bridges and communications. As one of the detachment’s soldiers Prokhor Bilokin wrote, on the morning of October 13, the detachment, angry after the defeat near Poltava, “having destroyed a brewery, a power station, and a mill... also burned down the two-story palace with 105 rooms”. Thus, everything that the Bolsheviks did not take out of Dykanka was irreversibly burned according to their instructions.

The latest act of vandalism arising from the policy of the Moscow government was carried out against the remains of the Kochubeys, in particular Vasyl Viktorovych, one of the first archeologist-numismatists in the Russian Empire. In 1932—1933, “activists” from Dykanka opened the sarcophagi in the crypt of St. Nicholas Church and took away items made of precious metals.

Descriptions of the robbery and looting of the Kochubeys’ palace a century ago are surprisingly reminiscent of current news from the temporarily occupied territories of our country. Stealing and removal of museum collections, and thoughtless wiping out of everything that could not be removed. For a hundred years, nothing has changed in the “methods” of treating Ukrainian cultural heritage on behalf of the Eastern invaders.

Anatoly Shcherban,

Doctor of Culturology, Head of the Department of History, Museum Studies and Monument Studies of the Kharkiv State Academy of Culture

Диканька. Спалений палац Кочубеїв. Фото 1924 року

Dykanka. The burnt palace of the Kochubeys Family. Photo of 1924

Джерело | Source: https://www.wikiwand.com/uk

Вироби із золота та срібла XVII—XVIII cтоліть, що 1914 року зберігалися в диканському палаці Кочубеїв. Оригінали фото віднайдено та опубліковано Володимиром Захаровим. Фотограф Я. Штейнберг. 1914 р.

Gold and silver artworks of the 17th—18th centuries, kept in the Dykanka Palace of the Kochubeys Family in 1914. The original images were found and published by Volodymyr Zakharov. Photo credit Yakov Steinberg. 1914

Музейна кімната. Джерело Фото із журналу «Столица и усадьба» (№ 66, 1916 рік)

Museum room. Photo from the magazine “Capital and Manor” (No. 66, 1916)

30.11.2022

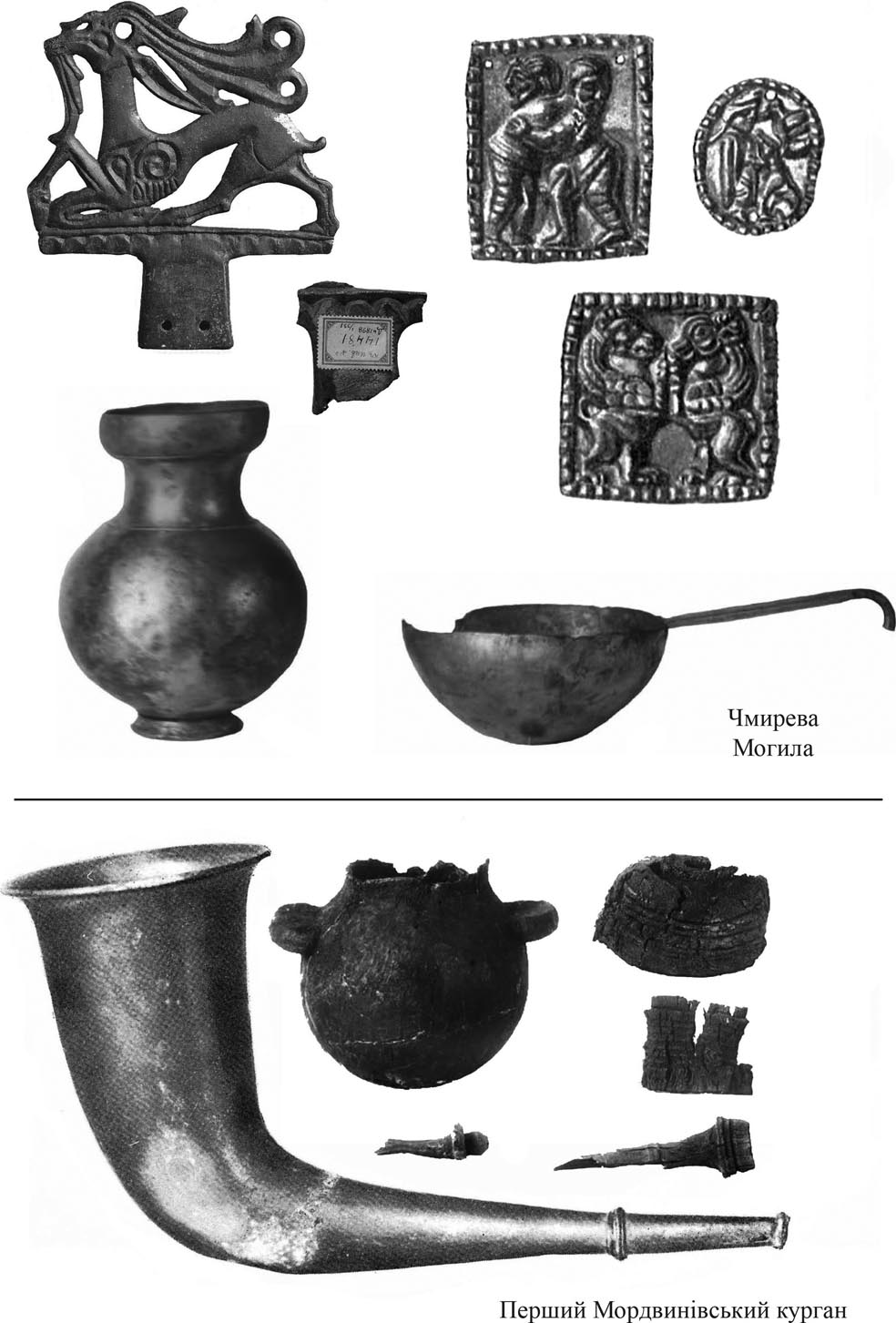

Випуск 9. Незавершена реституція

У взаємовідносинах між Україною та Росією відомо не надто багато прикладів результативної реституції. До цього часу наймасштабнішою за об’ємом залишається передача культурних цінностей з музеїв РСФРР до України, що відбулася 1932 року за результатами роботи та рішенням Паритетної комісії. Серед інших колекцій, в Україну з Державного Ермітажу передали деякі матеріали шести скіфських курганів, розкопаних у дореволюційний час, а саме — Литої Могили (Мельгуновський скарб; див. детальніше: http://vgosau.kiev.ua/novyny/proekty/1289-vypusk-3), Олександрополя, Шульгівки, Чмиревої Могили, Іллінецького та Першого Мордвинівського курганів. Але 31 січня 1932 р. українським представникам повністю повернули матеріали лише трьох курганів. Ще з трьох курганів — Олександрополя, Литої та Чмиревої могил — частина предметів, звісно ж найвидовищніших, була “тимчасово” залишена в Ермітажі для виготовлення гальванокопій.

Зокрема, з Литої Могили росіяни залишили знаменитий меч у піхвах із золотою обкладкою, золоту діадему, одну з 17 блях-пташок та пластину із зображенням мавпи та кількох птахів, срібні деталі притронного табурету, цвяхи та бронзові наконечники стріл, усього 17 предметів.

Із Чмиревої Могили для виготовлення гальванокопій відібрали за списком 25 предметів, з розкопок 1898 р. і 1909 р. Це бронзові, срібні та золоті предмети кінської оздоби, золоті пластинки — прикраси одягу, бронзове навершя (розкопки 1898 р.), намисто, прикраси, предмети побуту (розкопки 1909 р.). Крім цього, в Ермітажі за невідомих причин зосталися два предмети — кубок та черпачок, зі срібного «сервізу» Чмиревої Могили, що налічував 10 посудин, хоча до переліку предметів, що тимчасово залишаються для виготовлення гальванокопій, їх не внесли. Нарешті, в Ермітажі залишили і втулку одного із бронзових навершь, переданих до України.

Найрепрезентативнішою, серед затриманих для виготовлення гальванокопій, була колекція з Олександропільського кургану, що налічувала 80 предметів. Це навершя (9 екз.) та вирізні пластини (2 екз.), посуд та окремі його деталі (5 екз.), прикраси та деталі одягу — намисто та пронизки (15 екз.), нашивні пластинки-аплікації (21 екз.), підвіски та фрагменти прикрас (14 екз.), деталі кінської оздоби (15 екз.).

Зберігається в Ермітажі і частина предметів з Першого Мордвинівського кургану, колекцію якого росіяни повинні були передати повністю. Справа в тому, що під час передачі археологічних колекцій у 1926 р. з Державної академії історії матеріальної культури (ДАІМК, колишня імператорська археологічна комісія) до Ермітажу, частину предметів з Першого Мордвинівського кургану помилково атрибутували як знахідки з Кубані, й надали відповідні номери інвентарної групи «Ку». Це непорозуміння виправили вже після 1932 р. і розпізнані предмети перевели до групи «Дн» з порядковими номерами колекції Першого Мордвинівського кургану — Дн 1914 1/44—50. Цю колекцію склали дерев'яна посудина з двома ручками-упорами та фрагменти інших дерев'яних предметів — уламки циліндричної піксиди, виточеного стрижня (веретена?), коробочки та дощечок, а також кістяні пластинки з циркульним орнаментом і дві золоті трубочки-пронизки. Крім цього, встановлене походження з Першого Мордвинівського кургану срібного ритону, переданого в Ермітаж з ДАІМК разом з кубанськими колекціями в 1926 р.

Усі згадані предмети росіяни залишили в колекції Ермітажу і активно залучають до різних напрямків музейної роботи — експонують в постійній експозиції (зокрема — в залах Золотої та Діамантової комор), хизуються знахідками з території України на численних виїзних закордонних виставках, прикрашають привласненими історико-культурними цінностями різноманітні видання художніх альбомів та каталогів. Однак видається, що термін у 90 років є цілком достатнім для виготовлення якісних гальванокопій 122 предметів і ці знахідки, згідно з узгодженими правовими рішеннями, час уже повернути їх законному власнику — Музейному фонду України. Отже, директорові Ермітажу М. Б. Піотровському, очільникові протягом декількох останніх десятиліть, і, як нещодавно виявилося — палкому прихильнику спеціальних культурних операцій, — варто було б замислитися над проведенням однієї із таких операцій з повернення зазначених музейних предметів в Україну.

Леонід Бабенко,

старший науковий співробітник Харківського історичного музею імені М. Ф. Сумцова

Release 9. Incomplete restitution

There have been few examples of successful restitution in the relationship between Ukraine and Russia. Until now, the largest transfer of cultural values from the museums of the RSFSR to Ukraine took place in 1932 following the work and the decision of the Parity Commission. Among other collections, some materials from six Scythian burial mounds excavated in pre-revolutionary times were transmitted to Ukraine by the State Hermitage. Namely, there were artifacts from Lyta Mohyla (Melgunovsky treasure) (more details at the following link: http://vgosau.kiev.ua/novyny/proekty/1289-vypusk-3), Olexandropol, Shulgivka, Chmyreva Mohyla, Illinetsky and First Mordvynivsky burial mounds. However, on January 31, 1932, only the materials of the three kurgans were completely returned to the Ukrainian representatives. Part of the artifacts, of course, the most spectacular ones, from the other three burial mounds — Olexandropol, Lyta and Chmyreva Mohylas — were “temporarily” left in the Hermitage for making their galvanic copies.

In particular, the Russians retained the famous sword in a scabbard with a gold cover, a gold diadem, one of 17 plaques in the shape of birds and a plate with the image of a monkey and several birds, silver fragments of a throne stool, nails and bronze arrowheads — 17 items in total.

25 artifacts from the Chmyreva Mohyla, found during the excavations of 1898 and 1909, were selected according to the list, to create their galvanic copies. These were bronze, silver, and gold items of horse ornaments, gold plates — clothing ornaments, a bronze pole-top (excavations of 1898), a necklace, ornaments, and household items (excavations of 1909). In addition, for unknown reasons, two objects remained in the Hermitage — a cup and a ladle of the silver service found in the Chmyreva Mohyla, which consisted of ten pieces, although they were not included in the list of artifacts temporarily kept to make their galvanic copies. Finally, the socket of one of the bronze pole-tops, transmitted to Ukraine, was also left in the Hermitage.

The collection from the Olexandropol burial mound, which consisted of 80 objects, was the most representative among those kept for the production of galvanic copies. These were pole-tops (9 pieces) and cut-out plates (2 pieces), tableware and its separate parts (5 pieces), jewellery and details of clothing — necklaces and tubular beads (15 pieces), embroidered appliqué plates (21 pieces), pendants and fragments of jewellery (14 pieces), details of horse ornaments (15 pieces).

Part of the items from the First Mordvynivsky burial mound, the entire collection of which was supposed to be returned by the Russians, are also kept in the Hermitage. The fact is that during the transfer of archaeological collections in 1926 from the State Academy of the History of Material Culture (the former Imperial Archaeological Commission) to the Hermitage, part of the artifacts from the First Mordvynivsky burial mound were mistakenly attributed as the finds from the Kuban, and the corresponding numbers of the “Ku” inventory group were assigned to them. This misunderstanding was corrected already after 1932, and the identified objects were transferred to the “Dn” group with the respective serial numbers of the First Mordvynivsky Kurgan collection — Dn 1914 1/44—50. This collection consisted of a wooden vessel with two lug handles as well as fragments of other wooden objects — pieces of a cylindrical pyxide, a turned rod (spindle?), a little box and planches, as well as bone plates with a circular ornament and two gold tubular beads. In addition, it has been identified the provenance of the silver rhyton from the First Mordvynivsky Kurgan, transmitted to the Hermitage from the State Academy of the History of Material Culture together with the Kuban collections in 1926.