Випуск 8. Радянська влада і грабунок культурної спадщини Кочубеїв у Диканьці

Селище Диканька (тепер Полтавський район Полтавської області) відоме чи не на весь світ завдяки твору Миколи Гоголя. Окрасою Диканьки був маєток знаного та заможного козацько-дворянського роду Кочубеїв. Від кінця XVII століття цей маєток був місцем акумулювання різноманітних історико-культурних цінностей меморіального та мистецького характеру. У XІХ столітті колекції збагатилися і археологічними знахідками, оскільки власники активно долучилися до збирання та дослідження пам’яток давніх епох. Як свідчив у спогадах директор Полтавського музею Валентин Ніколаєв, котрий бачив приголомшуючі артефакти, що залишилися після від’їзду власників за кордон 1918 року, «приміщення палацу було буквально набите в окремих кімнатах картинами, старовинною бронзою, килимами, гобеленами, цінним фаянсом, фарфором і склом, старовинною зброєю і т. д. Величезну цінність мала прекрасна бібліотека…».

Зауважимо, що освічені жителі Диканьки, яких у селищі було чимало, та службовці місцевої економії не дозволили грабунку кочубеївської власності в 1917—1918 роках. Колегія з управління маєтками, до складу якої увійшли і представники від селянства, ретельно охороняла залишене Кочубеями майно. «А ні прутика, а ні гвинтика селяне не зачепили» Все уціліло, окрім кількох пістолетів та шабель. Працювала навіть палацова електростанція.

Але більшовицькі зайди не могли залишити таких багатств Україні. Спочатку навесні 1918 року «Перша совітська бригада або 8 полк» перевіз до Полтави три скрині срібних виробів (близько 480 кілограм, 670 предметів), які згодом відправили до Москви, й цінні артефакти зникли безслідно. Очевидно, що реквізиція відбувалася насильницьким шляхом. Відповідно, коли за «других совітів» (квітень 1919 року) до палацу з метою опису предметів старовини та відбору експонатів для Полтавського музею приїхали його співробітники археолог Михайло Рудинський і природознавець-пам’яткознавець Валентин Ніколаєв, їх хоч і допустили до колекцій, але тривалий час не погоджувалися на вивіз відібраних старожитностей і навіть погрожували вчинити самосуд над приїжджими. Місцеві селяни та службовці економії стверджували, що будь-яке вилучення є незаконним, адже «князь їм говорив, що рано чи пізно все його майно повинно відійти селянам і вони мають турбуватися про його охорону». Лише коли полтавські музейники посприяли створенню музею Диканьки в кількох кімнатах першого поверху палацу, диканці дозволили і допомогли вивезти найцінніші картини, ікони, зразки посуду, бронзи, зброї, книг, родинний архів. Почасти ці предмети й донині залишаються в Україні, але чимала їх частина зрештою була вивезена до РФ.

Певний час після приїзду полтавців новостворений диканський музей та пивоварний завод, як згадував активних учасник тих подій Яків Орисенко, охороняли «добровольці і слабі старики Диканського загону Авраменка М.». Але через підпал палац з висококоштовними речами перетворився на руїни. Існує кілька версій щодо того, хто зробив цей злочин. Найпоширенішу версію озвучив у спогадах Валентин Ніколаєв. Суть її така — осіннього дня з лісу виїхав загін озброєних вершників і став табором навколо палацу. Потім ці вершники сіли на коней, а через годину палац запалав. Диканці називали цих людей партизанами, а Валентин Ніколаєв уточнив, що це була «шайка грабіжників, що називали себе народними партизанами, котрі не тільки розтягнули ряд предметів, а й спалили весь палац і службові приміщення. Багато книг було кинуто в став».

Зі спогадів безпосереднього учасника цих подій, мешканця Решетилівки Прохора Білоконя, відомо, що вандали входили до загону Якова Огія (уродженця Кобеляцького повіту, члена УПСР (боротьбисти)). Незадовго перед подіями в Диканьці цей загін отримав директиву від членів Зафронтового бюро, підпорядкованого Центральному комітету Комуністичної партії більшовиків України, діючи в тилах денікінців дискредитувати їх, зривати мобілізацію, руйнувати мости та зв’язок. Уранці 13 жовтня цей загін, озлоблений після поразки під Полтавою, як писав один із його бійців Прохор Білокінь, «погромивши пивний завод, електростанцію, мельницю… спалив і дворець двоповерховий в 105 комнат». Таким чином, все що більшовики не вивезли з Диканьки, було за їхніми настановами спалено безповоротно.

Останній акт вандалізму, зумовлений відповідною політикою московського уряду, стався вже щодо останків Кочубеїв, в тому числі одного з перших в російській імперії археологів-нумізматів Василя Вікторовича. У 1932—1933 роках диканськими «активістами» було розкрито саркофаги в склепі Миколаївської церкви і забрано звідти вироби з дорогоцінних металів.

Описи пограбування та плюндрування палацу Кочубеїв століття тому напрочуд нагадують поточні новини з тимчасово окупованих територій нашої держави. Викрадення та вивезення музейних колекцій, бездумне винищення всього, що вивезти не вдалося. За сто років нічого не змінилося в «методах» ставлення до українського культурного спадку з боку східних зайд.

Анатолій Щербань,

доктор культурології, завідувач кафедри історії, музеєзнавства та пам'яткознавства Харківської державної академії культури

Release 8. Soviet government and the looting of the Kochubeys Family’s cultural property in Dykanka

The village of Dykanka (nowadays the Poltava district of the Poltava region) is known almost all over the world thanks to the work of Mykola Gogol. The estate of the well-known and wealthy Cossack-noble Kochubeys family was the decoration of Dykanka. Since the end of the 17th century, this estate has been a place of accumulation of various historical and cultural values of memorial and artistic importance. In the 19th century, the owners actively participated in collecting artworks and researching the sites of ancient eras and enriched their collections with archaeological finds. Valentyn Nikolaiev, the director of the Poltava Museum, described in his memoirs stunning artifacts that remained in the estate after the departure of the owners abroad in 1918: “a number of rooms in the palace were literally stuffed with paintings, ancient bronzes, carpets, tapestries, valuable faience, porcelain and glass, ancient weapons, etc. A wonderful library was of great value...”.

It should be noted that educated inhabitants of Dykanka, of whom there were many in the village, and employees of the local economy did not allow the looting of Kochubeys property in 1917—1918. The estate management board, which included representatives from the peasantry, carefully guarded the property left by the Kochubeys. “The peasants didn't touch a stick or a cog”. Everything survived, except for a few pistols and sabres. Even the palace power station was running.

Nevertheless, the Bolshevik invaders could not leave such treasures in Ukraine. First, in the spring of 1918, the “First Soviet Brigade or 8th Regiment” transported three boxes of silverware (670 items weighing about 480 kilograms,) to Poltava. Later, the valuable artifacts were sent to Moscow and disappeared without a trace. It is obvious that the requisition was carried out by force. Accordingly, during the “second Soviet period” (April 1919) the employees of the Poltava Museum, the archaeologist Mykhailo Rudynskyi and the naturalist and heritage expert Valentyn Nikolaiev, came to the palace to describe antiquities and select exhibits for the Museum. Although they were admitted to the collections, for a long time they did not agree to the removal of the selected antiquities and even threatened to lynch newcomers. Local peasants and economy officials claimed that any seizure was illegal, because “the prince told them that sooner or later all his property should go to the peasants so they should care about its protection”. Only when the Poltava museum workers contributed to the creation of the Dykanka Museum in several rooms on the ground floor of the palace, the Dykanka’s inhabitants allowed and helped to take out the most valuable paintings, icons, samples of dishes, bronzes, weapons, books, and the family archive. Some of these items remain in Ukraine to this day, but a significant part of them was eventually exported to the Russian Federation.

As recounted by Yakiv Orysenko, an active participant in those events, some time after the arrival of the Poltava citizens, the newly created Dykanka museum and brewery were guarded by “volunteers and weak old men of the Dykanka detachment led by M. Avramenko”. Due to arson, the palace with valuable things turned into ruins. There are several versions of who committed this crime. The most widespread version was mentioned by Valentyn Nikolaiev in his memoirs. On an autumn day, a detachment of armed horsemen left the forest and camped around the palace. Then these riders got on their horses, and an hour later the palace caught fire. The villagers called these people partisans, and Valentyn Nikolaiev clarified that it was “a gang of robbers, who called themselves national partisans. They not only looted a number of items, but also burned the entire palace and service premises. Many books were thrown into the pond”.

From the memories of Prokhor Bilokin, a resident of Reshetylivka and the immediate participant in the events, it is known that the vandals were from the detachment of Yakiv Ohii (a native of Kobelyatsky district, a member of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries). Shortly before the events in Dykanka, this detachment received a directive from the members of the Front Office, subordinate to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Bolsheviks of Ukraine, to act in the rear of the Denikinites in order to discredit them, disrupt mobilization, destroy bridges and communications. As one of the detachment’s soldiers Prokhor Bilokin wrote, on the morning of October 13, the detachment, angry after the defeat near Poltava, “having destroyed a brewery, a power station, and a mill... also burned down the two-story palace with 105 rooms”. Thus, everything that the Bolsheviks did not take out of Dykanka was irreversibly burned according to their instructions.

The latest act of vandalism arising from the policy of the Moscow government was carried out against the remains of the Kochubeys, in particular Vasyl Viktorovych, one of the first archeologist-numismatists in the Russian Empire. In 1932—1933, “activists” from Dykanka opened the sarcophagi in the crypt of St. Nicholas Church and took away items made of precious metals.

Descriptions of the robbery and looting of the Kochubeys’ palace a century ago are surprisingly reminiscent of current news from the temporarily occupied territories of our country. Stealing and removal of museum collections, and thoughtless wiping out of everything that could not be removed. For a hundred years, nothing has changed in the “methods” of treating Ukrainian cultural heritage on behalf of the Eastern invaders.

Anatoly Shcherban,

Doctor of Culturology, Head of the Department of History, Museum Studies and Monument Studies of the Kharkiv State Academy of Culture

Диканька. Спалений палац Кочубеїв. Фото 1924 року

Dykanka. The burnt palace of the Kochubeys Family. Photo of 1924

Джерело | Source: https://www.wikiwand.com/uk

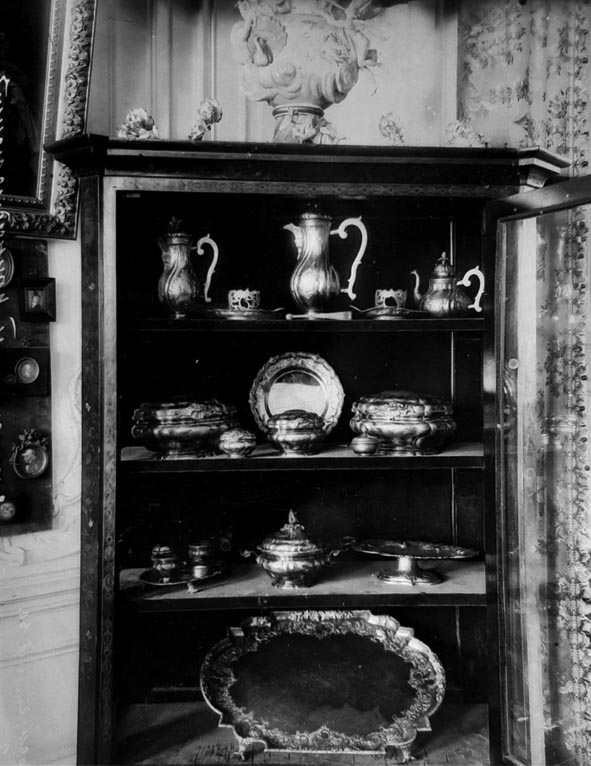

Вироби із золота та срібла XVII—XVIII cтоліть, що 1914 року зберігалися в диканському палаці Кочубеїв. Оригінали фото віднайдено та опубліковано Володимиром Захаровим. Фотограф Я. Штейнберг. 1914 р.

Gold and silver artworks of the 17th—18th centuries, kept in the Dykanka Palace of the Kochubeys Family in 1914. The original images were found and published by Volodymyr Zakharov. Photo credit Yakov Steinberg. 1914

Музейна кімната. Джерело Фото із журналу «Столица и усадьба» (№ 66, 1916 рік)

Museum room. Photo from the magazine “Capital and Manor” (No. 66, 1916)

30.11.2022

Проєкт здійснено за підтримки Стабілізаційного фонду культури й освіти Федерального міністерства закордонних справ Німеччини та Goethe-Institut. goethe.de

The project is funded by the Stabilisation Fund for Culture and Education of the German Federal Foreign Office and the Goethe-Institut. goethe.de